What's it like to live on a private street in Toronto?

Percy Street isn't like your street. This small stretch of Toronto road that runs south in a dog-legged kink from King Street to the Richmond Street ramp is one of the city's some 250 private streets and laneways. There's no gate, but the 35 residents here are just about as separate as it's possible to be in the city, and they like it like that.

"We call it the 'Republic of Percy,' it's kind of a joke," says Kali Hewitt-Blackie, co-owner of The Percy Bed & Breakfast at No. 6. "When you walk down the street it's like you're living in another land. It's not like Toronto, it's like something in England or someplace."

What really sets Percy apart is its lack of access to regular city services. There are no gates, barriers, or glaring warning signs, but snow, leaf, and garbage management are all arranged privately and paid for out of the resident's pockets. Even sewer maintenance costs are part of the experience shared by other private community residents like the home owners of Wychwood Park near St. Clair and Bathurst.

"We nominate people to do things," explains Hewitt-Blackie. We have a guy that's in charge of the bank account ... we have a little street signage committee, a street lighting committee, and we have one dealing with the rest of the things to do with Streetcar [the new condo that backs onto Percy.]"

Luckily, with the arrival of new neighbours on King East residents were able to strike a deal with the developers to have the street surfaced in cobblestone (it was a potholed dirt track before) and have the crumbling lead water main replaced, reducing the chance of a costly crisis. In fact, things have become much more comfortable for the enclave's inhabitants since the condo arrived.

"We used to shovel the street ourselves," recalls Hewitt-Blackie. "All the younger people would really help out ... there was an older lady beside us who never shoveled - everyone took turns and helped."

Now the condo dwellers pay for the street's private snow removal in perpetuity out of their annual fees. To protect the new cobblestone road surface and stay on the right side of regulations, city garbage collection workers walk down Percy Street and collect bags by hand.

"Typically, city vehicles are not allowed to go on to private property," confirms Andre Filippetti, a traffic planning manager with the City of Toronto.

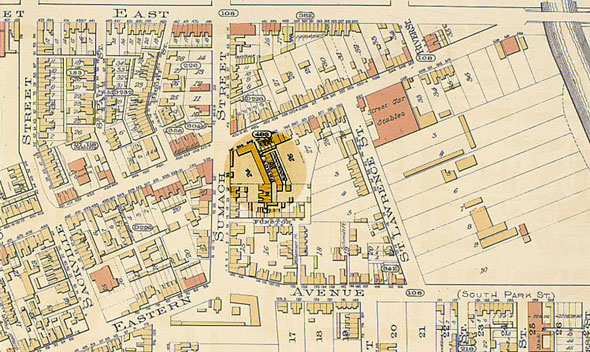

The little road has always been private. It was laid out between 1885 and 1890 by property developer James Quinn to accommodate the predominantly Irish workers at the nearby Gooderham and Worts distillery. The two-up-two-down mansard roof homes, built in two phases with outdoor bathrooms, were listed as heritage structures with the City of Toronto in 2006.

Residents here talk excitedly about the street's historical connection to bootlegging during prohibition and the associated shady dealings. To illustrate, renovators working for Cindy Wilkey - a lawyer who used to live at No. 5 - found $50,000 in cash at her former home in 1988.

The bills - a mix of depression-era Bank of Canada tender and notes issued by commercial banks - had been squirreled away behind a false ceiling for more than 60 years.

"They started counting out the money into piles. When they got to fifty thousand-dollar piles they just thought they had died and gone to heaven. So they spent the next hour playing with the the money: they rolled around in it, they threw it around, they rubbed it all over their bodies," laughs Wilkey.

Worth the equivalent of roughly $400,000 in today's money, the stash, all in small denominations, had been topped up as recently as the 1980s. The honest renovators handed the money over to the police and after a five-year court process wound up with a cut of the loot for themselves. The remainder was split between Wilkey and a previous owner of the house.

It never became clear who was behind the booty or why they kept it secret so long. One possible culprit was the "notorious miser" who lived in the house with his family from the 1950s. Though his daughter testified she never knew about the cash, her father worked as a delivery driver at the Don Valley Brick Works and had the means to transport goods.

It's also possible the money was hidden there by a neighbour or another owner entirely. "It's a mystery," laments Wilkey.

Police confirmed the bills weren't part of any known crime during their investigations but the money's provenance hints at the gritty reputation of old Corktown, and Percy Street in particular. Residents talk about illegal alcohol being hidden in crawlspaces and kids employed as lookouts for cops. The street fiercely defended its private status likely as a measure of defense from prying eyes.

Naturally, in a community where day-to-day chores need to be carefully managed for the collective good, there are a few unspoken rules: no parking on the street unless you have guests and everyone is encouraged to pitch in with the community garden, planting and harvesting herbs.

It's the sort of place where the community is always willing to rally.

Hewitt-Blackie remembers the evening she went out with her husband David and entrusted the small home to the guests. At 12:30, a call from one of the neighbours alerted Kali that a raucous party had broken out, keeping everyone awake.

When the couple returned to break things up, the offers of help from the other residents of Percy Street were immediately forthcoming. "When some shit happens your neighbours are there," she says. "We don't bug each other but we go to each other if there's problems. It's a real old-school community."

Curious onlookers and wanderers are welcome (there's public park at the foot of the street) but loiterers are looked on with suspicion by Percy Street's monitor, Sharon. "She'll come out and say 'Can I help you?,' but she does that for everybody, and she says it in a very nice way."

Everyone is on first name terms. There's no restrictions on who's allowed to buy or rent but often homes are sold to family, friends, or other people with some connection to the street. In local lore, a former Republic resident, a real estate agent, closed the sale of her home while giving birth.

Hewitt-Blackie bought the home she would renovate into a bed and breakfast with her husband after living on nearby Sumach Street. The contractor the couple hired stayed in the home for a short time and eventually bought the property next door. That's how things seem to go around here.

Anyone wanting to organize the secession of their own street will have a problem. The city only allows residents to purchase laneways - always at market value - providing council gives permission and the proposal clears the necessary legal hurdles. Organized properly, private living seems to have its perks.

"I feel like I'm living in downtown Toronto in the country with a bunch of neighbours. And you know what's wild? We get along," beams Hewitt-Blackie.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: Chris Bateman, City of Toronto Archives, and Patrick Cummins/blogTO Flickr pool

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments