A history of women's rights in Toronto

Over the last three months, women in Toronto have taken to the streets in support of women’s rights and gender equality. Whether they were marching in solidarity with the Women’s March on Washington or commemorating International Women’s Day, women in Toronto have a longstanding tradition of advocating for gender equality across Canada.

For women in Toronto, the struggle for equal and legal rights included a difficult set of processes that shaped the character of the city.

In fact, the movement for women’s rights in Canada began as a response to the changing economic and social conditions facilitated by industrialization in the nineteenth century.

As education became more accessible, people moved from rural to urban centres, and the economic status of many Canadian families changed, women gained (some) mobility and pushed for access to equal rights.

While many people think that the campaign for women’s rights in Canada was largely an issue about suffrage and gaining the right to vote, it was much more than this.

Many of the women’s organizations that emerged in the mid-19th century also called for better access to economic independence and improved social conditions for women.

In 1871, the Married Women's Property Act of Ontario was passed and gave married women the right to hold their own earnings and wages, along with any profits from the businesses they owned.

Recognizing that a woman’s legal identity could be separate from a man's, early property laws inspired the creation of several women’s rights organizations across the city.

Emily Stowe. Photo via the E.J. Pratt Library.

Largely encouraging middle-class ideals of respectability and femininity, the Toronto Women’s Literary Club stood as one such organization. Led by Dr. Emily Stowe in 1876, the Literary Club worked to address the need for women to gain access to higher education, better working conditions, and entrance to the political sphere.

In 1884, the Literary Club changed its name to the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association (CWSA) to reflect its expanded mandate to support women’s suffrage and enfranchisement.

As part of CWSA’s advocacy work, Toronto women cast their first votes in the city’s municipal elections on January 4, 1886.

While women gained a small victory by obtaining the right to vote in Toronto municipal elections, it was not until 1918 that Prime Minister Robert Borden granted the full franchise to women, partially as a response to their participation in the war effort.

As women continued their support and wartime participation into the Second World War, their mobilization around rights for equal access to work and pay also rose.

Women joined unions in increasing numbers and put pressure on provincial and federal governments to enact legislation for working women.

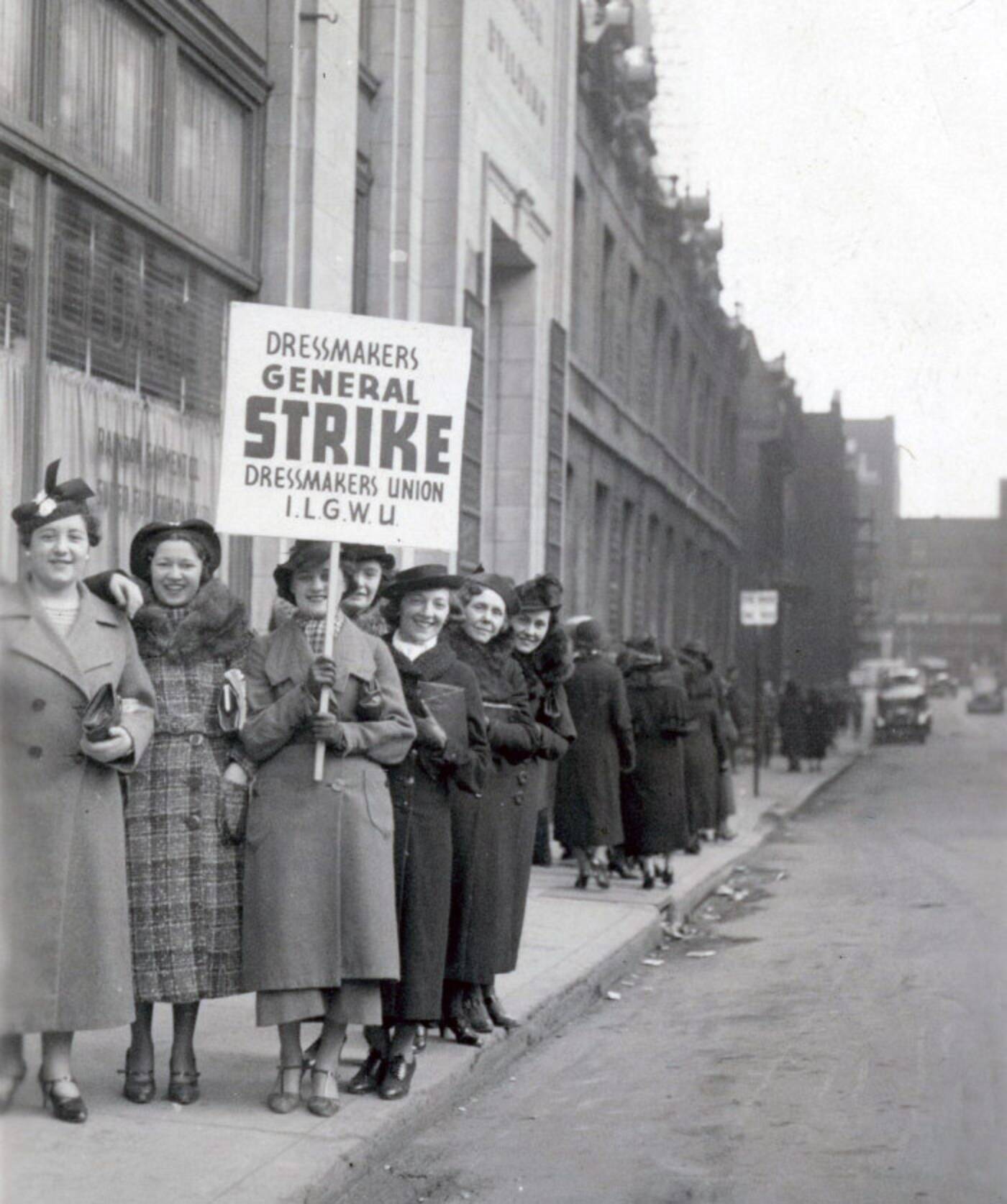

Dressmakers Union I.L.G.W.U, 1931. Photo via the Ontario Jewish Archives.

When the Toronto local of International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) went on strike in 1931, they highlighted the wage inequality and workplace harassment that many immigrant workers faced in Toronto.

By the time the province passed the Female Employees Fair Remuneration Act in 1951, women’s labour and union activities were at all time high and demands focusing on equal pay for equal work were championed by several women’s union organizations.

However, long standing racial and gender hierarchies in Canadian society also meant that not everyone was equally included in the national vision for women’s rights.

In fact, Indigenous women did not obtain the right to vote until 1960 when the Canadian Bill of Rights granted them the federal vote without losing their Indian status.

As part of the racial and gender discrimination reinforced through the Indian Act, Indigenous women found themselves fighting for political participation and equal rights after their traditional political systems were destabilized under colonial state practices.

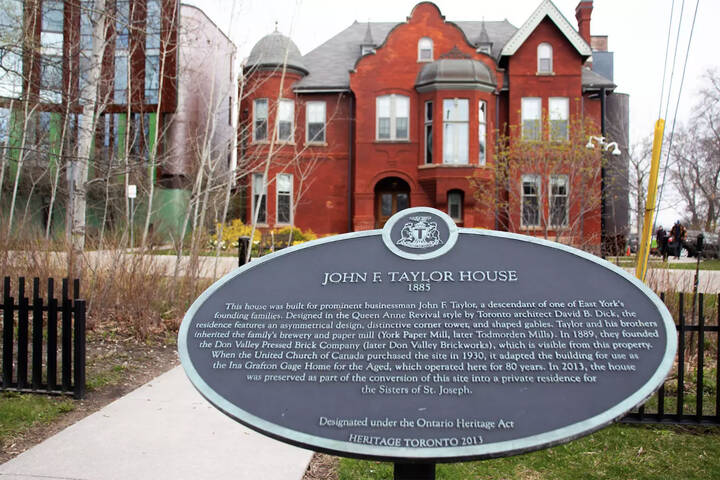

Native Canadian Centre of Toronto. Photo via First Story Blog.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous community members, many of whom were women, established the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto and the Ladies’ Auxiliary in 1963.

Working to instill cultural pride and access to educational and communal spaces, women within these organizations reflected growing Indigenous activist networks.

Even as women’s rights activism gained mobility in the 1960s with Royal Commission on the Status of Women, Black women in Toronto continued to fight against discrimination in housing, education and labour.

Black women’s activism in the city took on many forms and was viewed not only as a way to assert their own womanhood but also as a way to ensure community and cultural survival.

Congress of Black Women of Canada, Toronto Chapter. Photo via the Toronto Public Library.

Building on earlier organizations such as the Eureka Club in Toronto and the Toronto Chapter of the Congress of Black Women of Canada, the Black Women’s Collective worked in the 1980s to tackle intersectional issues facing women of colour and called for broader representation in national women’s organizations.

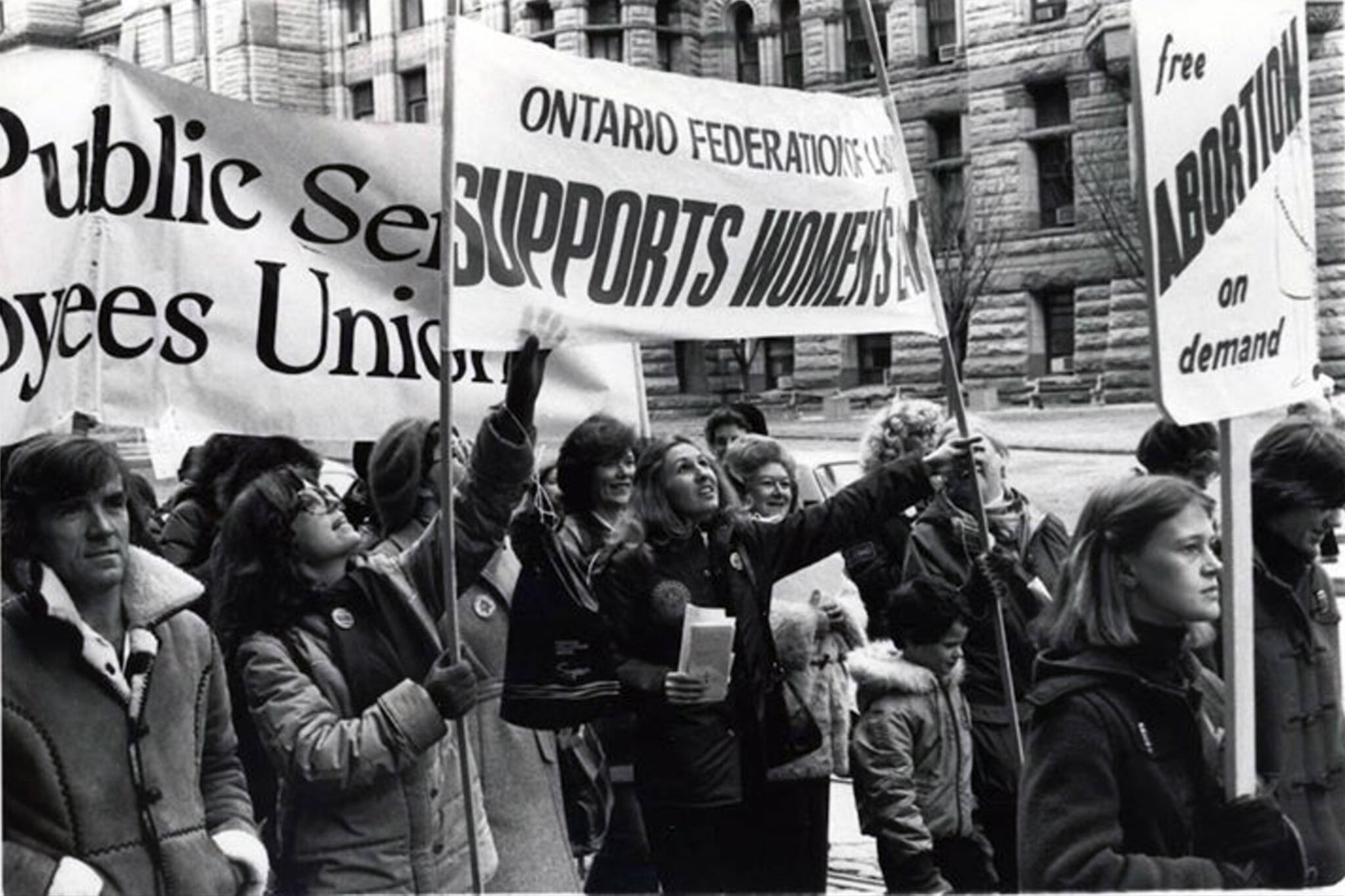

As the 1980s supported second wave feminists and their fight for reproductive rights, the historic 1988 Supreme Court of Canada ruling declared that prohibiting abortion was unconstitutional.

Women activists across the city celebrated the legal acknowledgement of a woman’s right to her own body.

By the 1990s and into the 21st century, women’s rights activists were highlighting the growing effects of gender and globalization.

Tackling issues of poverty, human rights, violence against women, and transphobia, Toronto women utilized digital platforms and built coalitions to continue the fight for women’s rights.

The Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action exemplifies this growing group of organizations working to advocate for national policy changes around international human rights.

As women in Toronto continue to fight against the legacies of colonialism, racism, sexism and global interests that reinforce structures of inequality, they do so through a series of complex understandings and motivations interconnected to their experiences in the city.

Thanks to the CBC for sponsoring this post.

Writing by Funké Aladejebi, an historian who researches the lives of Black Canadian women. She teaches in African Canadian history at York University.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments