How the TTC sullied the reputation of LRT (Part I)

Will Toronto's transit imbroglio never end? With the Prime Minister now being squeezed for a soundbite, Mayor Ford's war on streetcars has now spread from town hall meetings to Queens Park to Ottawa. Not since a certain other suburban-oriented Mayor called in the feds to clear a snowdrift has a Toronto issue garnered so much local, regional and national attention.

That said, there is a puzzling and nasty undertone to much of the discussion. It might be one thing for there to be debate over appropriate levels of national or provincial funding for a single city (albeit a city that in turn is an engine for the national and provincial economy). Or perhaps it could be expected to see people argue at length if there were some significant legal or environmental issue involved such as condemnation-property rights or accessibility. But these factors aren't even on the table — instead it's about subways vs light rail transit, and how much the people who love subways hate LRT. Regardless of how staged and silly it was for a room full of people to boo and jeer the very mention of LRT, the fact that such an event could even occur in Toronto was remarkable.

What happened? How did the very city that is internationally known for its streetcars end up being full of Randall O'Toole clones? Rob Ford could not have singlehandedly created such sentiment in a mere two years; something cleary went horribly wrong over a long period of time to build the kindling that Ford simply put a match to. Here's Part One of how the TTC itself sullied the reputation of surface rail in Toronto:

Bad Semantics

Public transit terminology could be a thesis topic for linguists. Many "subways" are not entirely underground. Nearly a third of the huge New York subway system, for example, is elevated above the roadway. Some LRT systems like Boston and Newark have historically been called "subways" because of a central tunnel, even though the vehicles later emerge to run on the surface in the medians of streets. Others such as Houston and Minneapolis use the word "metro" even though their LRT systems are nothing of the sort.

Further muddying the waters, some LRT systems have names derived from streetcars, and some streetcar systems have names that sound more like subways. Confused yet?

Canadian cities make the situation even worse. Vancouver has a medium capacity light-metro "Skytrain" that is not a subway, nor a traditional train, nor even necessarily found in the sky (there are extensive underground sections). Calgary and Ottawa call their Light Rail Vehicles "trains." Montreal has a metro that runs entirely underground, but on rubber wheels . And then there is Toronto.

"Streetcar" is a very old and clearly defined word in Toronto — this was never a "trolley" or "tram" town — and most of the streetcar lines in the city run very much as they did a century ago, in mixed traffic, in vehicles directly descended

from the first streetcars. But as streetcar lines were rebuilt or added in recent decades, the TTC got too clever by half and tried to slap the LRT tag onto lines that were very much still traditional streetcar routes.

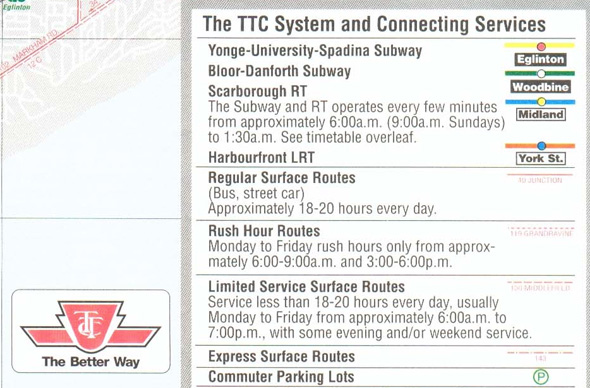

Remember the "Harbourfront LRT," a line so symbolically traditional that it used restored PCC cars? The 510 Spadina has also been called "LRT" at times. The recent rebuilding of St. Clair did not improve matters, being widely branded as LRT at the time despite the fact that the TTC now swears it is not an LRT.

And what do those letters stand for, anyway? The TTC calls its elevated medium-capacity light metro in Scarborough an "RT," or "Rapid Transit" But this is not the same "RT" as found in "LRT," which in Toronto has sometimes meant "light rail transit" and sometimes "light rapid transit" and sometimes, pardoxically, "streetcar rapid transit."

On the rest of the continent, where a city has both LRT and streetcars the linguistic distinction is clear. You have your Portland Light Rail, and your Portland Streetcar. Same goes for the Seattle Light Rail and the Seattle Streetcar. But in Toronto it's just a jumbled mash-up. Nothing sums this up more than this reference in a tourist guide to the "Spadina LRT Streetcar". No wonder Transit City's LRT lines had such a tough time finding acceptance in this tongue-tied town.

Worse Maps

All rails are not created equal, at least in the minds of TTC mapmakers. While subways and the RT have their own simplified map and are clearly highlighted on the overall "System Map", good luck finding the 75 km of streetcar tracks on any TTC cartographic product. A visitor looking at the TTC's own Downtown Map blowup would certainly have no idea which thin red line was a bus and which depicted the ten streetcar routes 250,000 people each day — they are all the same color and most are the same linetype. The tiny legend should not normally be necessary for someone simply searching for major routes but even this is of little help — it only mentions "streetcar rapid transit" (for Spadina/Queen's Quay and St. Clair) and ignores all other streetcars completely. One would literally have to have prior knowledge to find any surface rail line when traveling on the TTC — it simply does not exist on paper, anywhere.

The topographic inertia has been hard to escape. In the early 1990s, the new "Harbourfront LRT" briefly appears on maps as a higher-order transit line, only to disappear a few years later once the line was expanded to include Spadina. Nothing changed in the service itself — it just went back into hiding on the map.

This is patently bizarre. No other public transit system in North America with any kind of rail line fails to highlight it as such on a system guide or subway map, even when the rails fall under different modes and agencies. Here are examples from Seattle, Portland, Philadelphia and New Orleans. The suburban streetcar section of the Boston T's Red Line is lithographically shown as equivalent to the subway it connects to. Clearly the steel wheels in these towns are higher-order transit, even when running in mixed transit.

Which is entirely the point. Besides higher carrying capacity, rails on the ground represent certainty for residents, businesses and property investors. This is why many academic papers have been written on the use of streetcars as an urban development tool. They also are easy to understand for visitors, who can board a vehicle feeling confident about the destination. Pop quiz: have you ever visited a big city as a tourist and hopped on trains or trams but not once boarded a bus? Even though transfers are free and the buses go everywhere, often at comparable speed to a subway for short distances? Think about it for a moment.

If you want a logical, practical, easy-to-understand higher-order Toronto transit map you have to look to hobbyists rather than the TTC. The internet is full of the kind of map that puts all rails on their rightful pedestal. The concept is hardly radical.

Part I Summary

Toronto is blessed with the continent's largest streetcar system yet can't figure out how to describe it. Cartographically misrepresented and badged with a lexicon of misleading labels, it's no wonder light rail had a bad name in Hogtown before the first modern LRT line could even be built. Riders of the steel ribbons may know better, but you can hardly blame a car-commuting citizen of the former boroughs for thinking that any kind of surface rail is nothing better than a bus since every representation from the TTC has equated the two modes. This deeply toxic association has proven very difficult to undo in the minds of those who are less than obsessive about their transit maps and terminology. No matter how many times someone points out that the planned LRT routes on Finch or Sheppard would, say, have more distant station stops or not take up auto lanes, a number of people will nonetheless think of the downtown streetcars. It's enough to make one want to cry out.

Coming Up in Part Two - Operations, tourism and the sad, sorry tale of the RT

Writing by Larry Green

Lead photo by picturenarrative in the blogTO Flickr pool. 1993 Route Map via Transit Toronto and Streetcar map via Wikimedia Commons.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments