Nostalgia Tripping: remembering Regent Park

Oak Street, running through the middle of the north section of Regent Park, is one of the oldest streets in Toronto. As with the neighbourhood itself, it has witnessed substantial changes in the last sixty years, and is currently in the process of transformation.

Like the surrounding area, it has mostly been associated with poverty and poor planning, stemming from what, according to John Sewell, was originally intended to be an idyllic combination of urban renewal and social reform. The Toronto version of postwar social reform dictated that existing neighbourhoods be razed and replaced instead of revitalized in less drastic ways.

There are, of course, other streets in this oft-stigmatized neighbourhood, but Oak was at the core of the concerns of the social reformers in the late 1940s. It marked the centre of what they referred to as a "blighted area," a sore on the map of a thriving, postwar city, whose inhabitants were gradually relocating to the expanding suburbs.

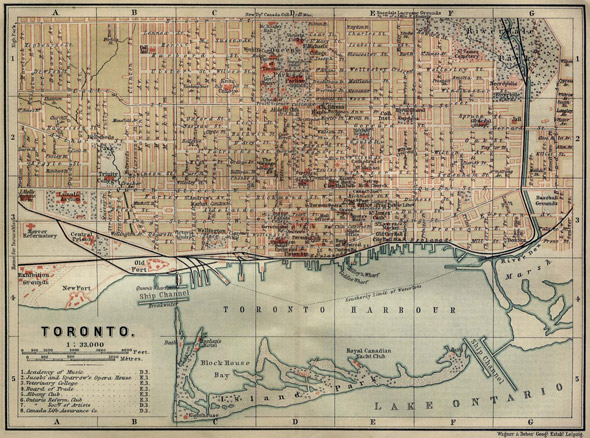

This "blemish," known as Cabbagetown before its rechristening as Regent Park (Sewell asserts that the renewed area was named after the prestigious Regent's Park in London, UK), was bounded by Gerrard Street to the north, Dundas Street to the south, Parliament Street to the east, and the Don River in the west. As a volunteer at the Cabbagetown/Regent Park Community Museum, to me, it's clear that even to this day, the name has been a source of much debate, controversy, and acrimony.

Rhe most vocal proponents of these traditional boundaries of the newly planned neighbourhood were Hugh Garner, the writer of Cabbagetown, and J.V. McAree, the writer of Cabbagetown Store, the latter of whom stated that the new name was "properly disallowed and resented" by the old Cabbagetowners.

According to Goad's 1890 Fire Insurance Atlas of Toronto and the 1894 map above, Oak Street was laid out from Parliament Street in the west to the Don River in the east. Its inhabitants were skilled and unskilled workers, who, like their neighbours living on other streets in the neighbourhood, were employed in nearby factories and other commercial enterprises. Some of their places of employment included Gooderham and Worts Distillery and the Gerhard Heintzman Piano Company (amongst others).

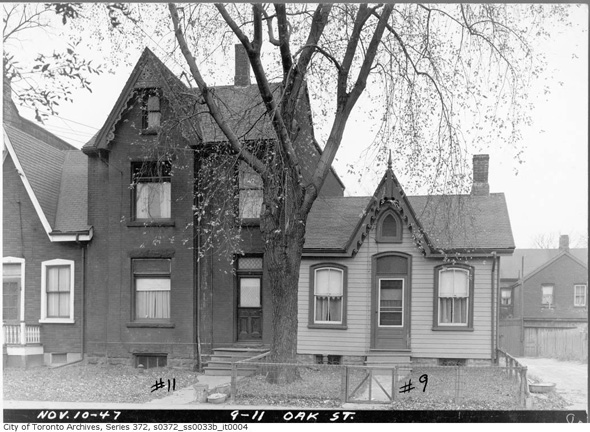

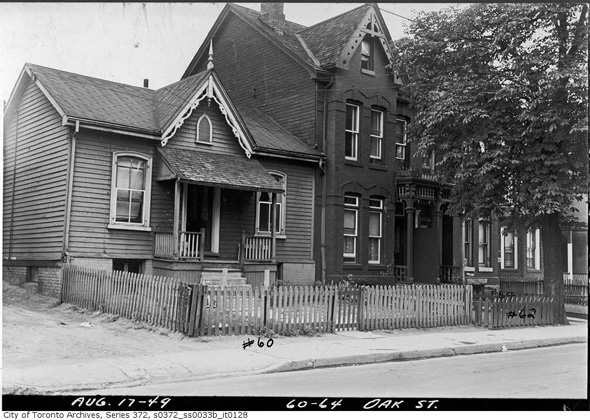

Archival photographs reveal that, architecturally speaking, the houses on Oak bear a close resemblance to the residential dwellings located north of Gerrard. According to George Rust-D'Eye's Cabbagetown Remembered, however, the area south Gerrard of was dominated by mostly one- and one-and-a-half story frame structures, known as "workers' cottages," built towards the end of the nineteenth century, when there were no building permits or minimum building standards.

As a result, they were of very poor quality, and by the end of World War I, they started to deteriorate. These houses had no insulation and tended to be cold in winter and hot in the summer. Most Cabbagetowners were tenants, and the absentee landlords, living outside of the area, rarely maintained their properties.

In 1957, the National Film Board released a documentary entitled Farewell Oak Street, narrated by Lorne Greene. The short black and white film depicts a working-class family, who are relocated from their substandard, nineteenth-century dwelling, and transferred to a bright, spacious apartment equipped with the latest conveniences of postwar life. The narrator informs us that they were forced to live "for the lack of anything better, not by choice."

He's alluding to the shortage of housing Toronto experienced after the war, and the film depicts the effects of a lack of suitable living space: lack of privacy, overcrowding, and generally, unhealthy living conditions -- all of which putatively lead to the disintegration of a proper family life. White-Picket Dreams, a short CBC documentary from the late 1940s that mentions Regent Park, illustrates the historical and social context in question well -- here was the marriage of two ideologies, slum clearance and urban renewal.

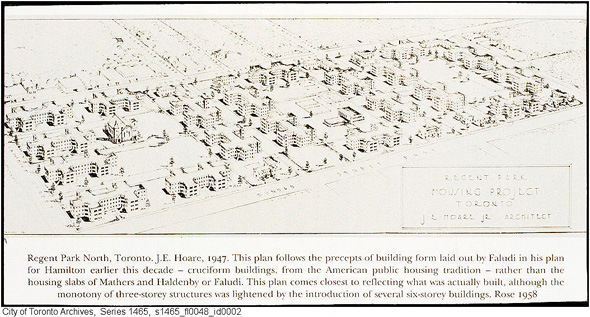

According to the J.E. Hoare's plan for Regent Park, Oak Street was originally designed as a through street, but it was eventually closed off in the centre of the neighbourhood. Still its east and west ends remained. This insular plan was in tune with the ideals of the influential Garden City movement from the UK, which dictated that houses should be free-standing, with no relationship to the street.

Such a plan appealed to the Housing Authority of Toronto, which wanted to create green space where there had been none before. Over time, however, parking lots colonized the parkland, and the fact that the inner streets did not connect to the municipal roads outside of the area made it challenging for emergency services and visitors to navigate. More importantly, closing off Oak and the rest of inner streets greatly contributed to the physical and social isolation of Regent Park residents. Many believe that this is one of the primary reasons why the project ultimately failed as a social experiment.

The revitalization plan, announced in 2005, stipulates that Oak, like other streets, is to be reconstructed as a thorough road.

Let us hope that the new approach of constructing mixed-income communities in the place of failed urban and social reforms is able to recreate and sustain Regent Park as a livable neighbourhood.

Photographs of Oak Street and J. E. Hoare's plan for Regent Park are from the Toronto Archives, with fond and series information located at the bottom of the image. 1894 Toronto Map sourced from the Wikimedia Commons. And, the photo of a Regent Park apartment building is by Erik Twight of Flickr.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments