That time Toronto blew up a historic ship just for fun

Somewhere out beyond the breakers at Sunnyside Beach lies the zebra mussel-encrusted wreck of the Lyman M. Davis, the last wooden schooner of the Great Lakes. Though countless ships met a watery fate in storms or in accidents on Lake Ontario, the charred hull of this majestic ship sits partially covered by silt on the lake bed because Depression-era beach-goers wanted something fun to blow up one summer evening in 1934.

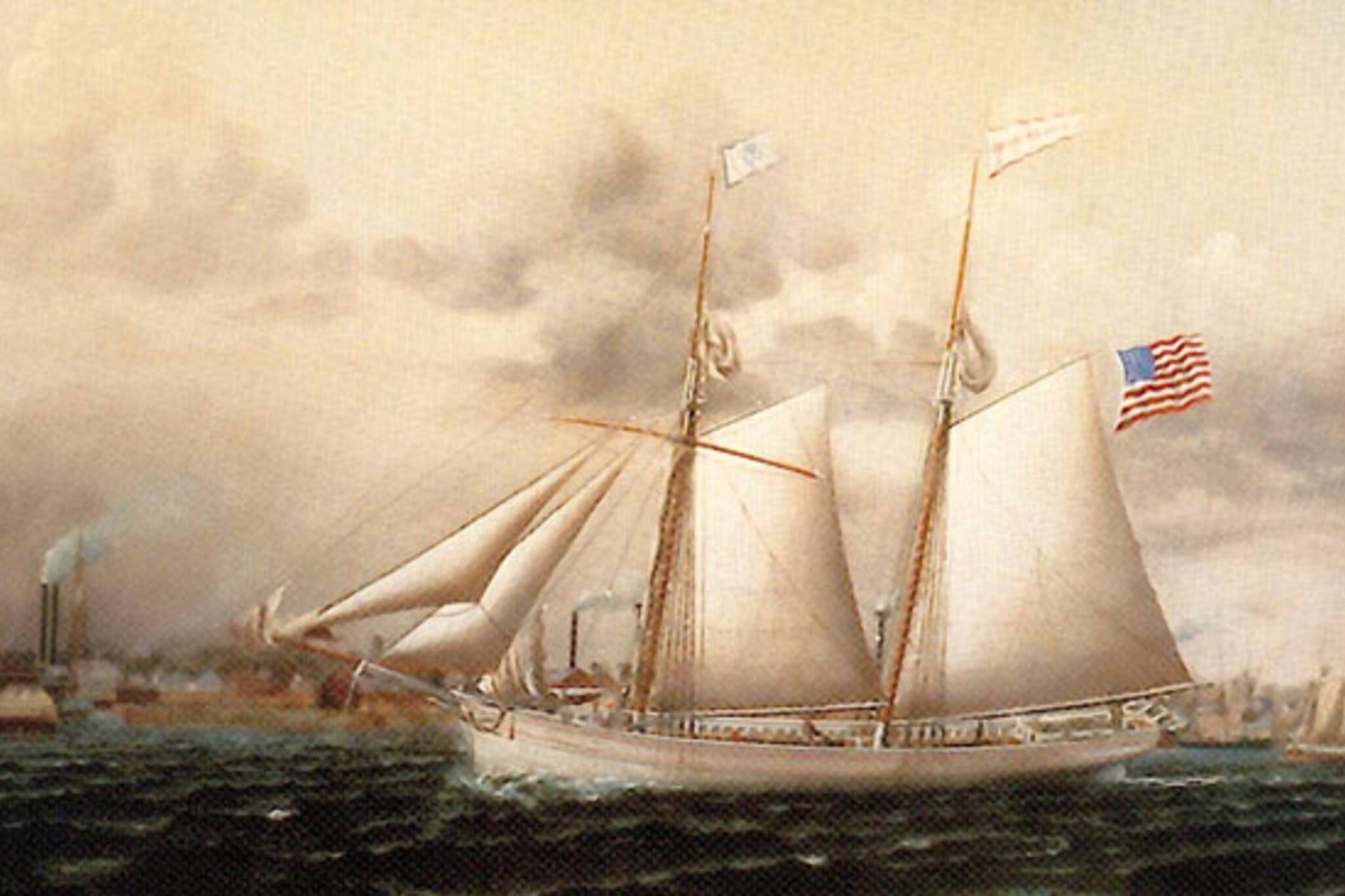

The Lyman M. Davis was built in Muskegon, Michigan, a small town tucked inside a natural harbour on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, in 1873. At nearly 40-metres front to back and with room for 225 tons of cargo, the vessel, with its twin masts and multitude of sails, was built to carry vast stacks of white pine from the Upper Peninsula to Chicago during the restoration that followed the city's great fire.

At its it was considered one of the fastest schooners in its class. In the days before steamers, wind-powered vessels were the backbone of the Great Lakes shipping industry. Hundreds of them darted between port cities like Toronto, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Detroit.

The ship was sold into Canadian ownership in 1913, according to wrecksite.eu, a website that records the details of wrecked ships from across the world, where it hauled stones and coal across Lake Ontario from Oswego, New York to Napanee and Kingston.

Steamers could carry significantly larger loads than schooners and ships like the Davis became less popular with shipping companies in the '20s. With little scrap value, many were filled with stones and sunk. In 1933, the Davis was valued at just $1,400, about $25,000 in today's money, and awaited a similar fate.

In the Depression years of the early '30s, management at Sunnyside Amusement Park had hit on a sure-fire way to coax reluctant punters inside: burning things. Big things. Starting in 1929, the park burned a ship every summer, starting with the ferry John Hanlan and later the Jasmine, Clark Bros., Luella, Primrose, Toronto Sun historian Mike Filey notes in his book I Remember Sunnyside: The Rise & Fall of a Magical Era

It's not clear how the Davis wound up on Sunnyside's dead pool, but it was Toronto's centennial year, and presumably those in charge felt destroying part of Canada's maritime heritage was somehow fitting.

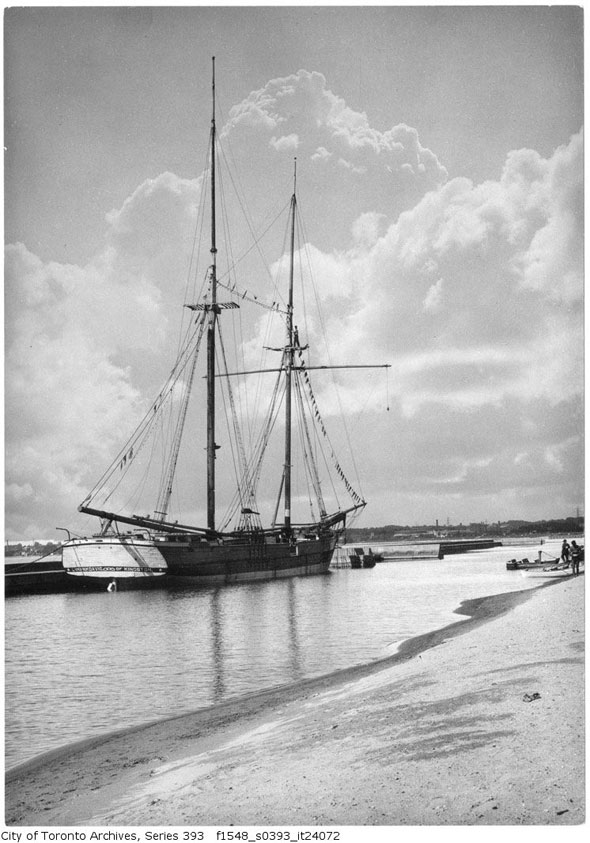

The doomed ship was towed to the breakwall off Sunnyside Beach in late 1933, just a stone's throw from the packed roller coaster and giant swimming tank. Workers stripped the rigging, sails, anything left of value, leaving it a dry wooden skeleton, a perfect tinderbox, through the winter.

The decision to burn the ship wasn't without controversy. Toronto Evening Telegram editor and marine historian Charles Henry Jeremiah "C.H.J." Snider led a movement to halt the pyre with the help of seasoned schooner man Captain John Williams.

"Burning that old schooner would be an act of savagery," Williams said in the Telegram. "It would be on par with tying cans to the tail of some faithful old dog that had outlived its usefulness, and kicking him out on the street just to see how fast he would run."

5,700 people signed a petitioned asking the city's board of control to buy the ship and gift it to the local sea scouts, but controller and later mayor William D. Robbins balked at the cost, suggesting the Davis could be saved if all the signatories had chipped in a quarter instead.

Ultimately, attempts to halt the spectacle were in vain. In mid-summer 1934, workers stuffed the deck and holds with crates of dry wood and straw, firework experts lined every surface with "bombs and rockets," and eight barrels of incendiary coal-oil was poured through the ship in anticipation of the all-important spark.

Sunnyside revelled in the destruction they were about to wreak. "The last remaining sailing vessel on the Great Lakes is disappearing ... the era of a host of gallant ships comes to an end," an read an advert that also contained a gratuitous description of what the fire would be like.

250,000 people (or so the concessionaires boasted) lined the shore on the big night. Entry was free - the real money was in sales of hot dogs, peanuts, popcorn, and Cracker Jacks - and a good spot on the beach was prime real estate. As the crowd took their places the Davis was towed to its final destination.

"... the vessel's destruction had the character of an execution. She was made to take that last short voyage, even as a condemned person is made to walk to the gallows, and she did in the ignominious tow of a sooty tug," wrote the Telegram, which, under the editorial control of the boat-loving C.H.J. Snider, took the loss extremely personally.

And then they lit the fuse.

The ship erupted in flame, sending an orange light dancing across the faces of the gathered of onlookers. Fireworks mounted to the rigging shot hundreds of metres into the air and miniature bombs popped, burst, and crackled like gunfire.

"For more than an hour the great crowd stood fascinated by the roaring flames. They were more than fire-struck. They were held by the same type of spell which in olden days drew morbid crowds to the public Toronto hangings," the Telegram wrote.

"Even the most thoughtless of the watchers saw in the sinking vessel something more than the destruction of an inanimate thing. They had a feeling that out in the centre of the oil fed flames, the bursting bombs and roaring rockets, a personality, and what, until then, had been a living memory of inland sailing fleets, was quickly dying."

Despite the ravages of the fire the Davis failed to sink. In the early hours of the morning a tug towed the hull out to deep water and a final bomb, dropped through a hole in the deck, sent it "hot and steaming beneath the quiet ripples of the outer bay," leaving only the scorched transom floating on the waves.

The wooden panel that once formed the flat rear of the Davis eventually washed up on the Toronto Islands where it saw use as a rest area for bathers, but the doomed ship wasn't seen again for 50 years.

In September 1983, a team of divers including Robert Wadsworth found the hull 40 metres down, half submerged in silt during a dive with Save Ontario Shipwrecks, a provincial organization dedicated to the study and preservation of Ontario's maritime heritage.

It was fitting the Wadsworth was among the first to visit the wreck. His great-great grandparents had sailed on the Davis as a cook and deck hand. His grandmother, Pauline Wadsworth, spent six years on board as a child.

"I wouldn't come to see it burn," she told The Toronto Star. "Neither would my mother or father."

"She was a magnificent ship, she really was."

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: Wikimedia Commons, City of Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments