A brief history of the Don Valley Brick Works

Toronto was built by the Don River and the valley it carved--literally. The substantial clay and shale deposits found in the bottom of the river valley were quarried, shaped, baked and stacked for buildings such as Casa Loma, Massey Hall and the Ontario Legislature at Queen's Park. Elsewhere in Canada, Don brick went into the Acadia Apartments in Montreal and the T. Eaton Buildings in Winnipeg and Moncton.

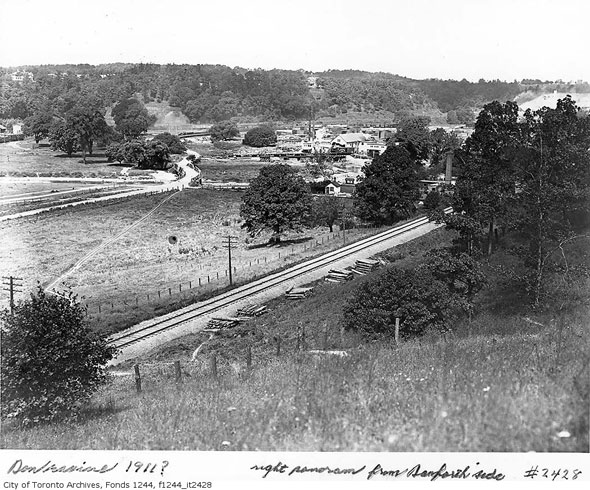

Thanks to fortuitous geography, the material that William Taylor discovered at the foot of Moore Park Ravine while staking out a fence for a paper mill in 1882 was absolutely perfect for construction. Within a few years, a small divot in the ground had evolved into a full-scale quarry and production facility turning out hundreds of thousands of bricks every day.

If right now you're sitting in a building built before the second world war, there's a chance the walls came from the Don Valley.

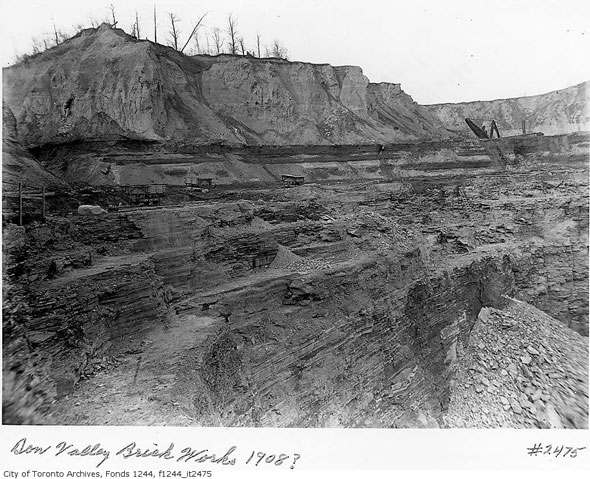

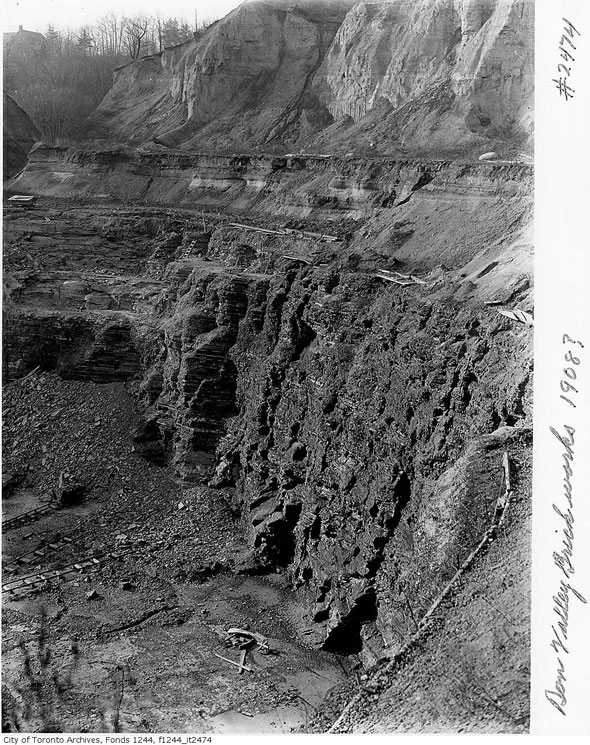

Don Valley bricks were the final step in a 400 million year process. Long before human history began, a tropical ocean covered what is now Ontario. Over eons, the weight of the water compressed the soft mud of the ocean floor into shale, a fine-grained sedimentary rock.

Fast forward an eternity or so, and meltwater from the receding Laurentide Ice Sheet that once covered much of North America had formed a river mouth roughly at the site of the brick works. With the frigid water came vast amounts of clay in the form of silt, which was perfect material for bricks.

In 1892, while working at Todmorden Mills, his father's paper factory, William Taylor was digging holes to support a fence around the edge of the property when his shovel turfed up a lump of good quality clay. Clearly a shrewd businessman, Taylor took a sample of the material to another brick works in Toronto to have it tested.

As you've probably guessed, the bricks were good. Within five years Taylor and his two brothers, William and George, had secured the land and started the Don Valley Brick Works and quarry to capitalize on his discovery.

As the business grew, the Don Valley Pressed Brick Company produced three types of brick: "soft mud," a mix of clay and river water, "dry press," moulded shale, and "stiff mud," a mix of clay and shale with water. The Taylors' company was the only one to produce all three types of brick at the same time Canada. The quality was considered so high that the bricks won prizes at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair and 1984 Toronto Industrial Fair. Shortly after, in 1901, the Taylors sold the business to their brother-in-law, Robert Davies.

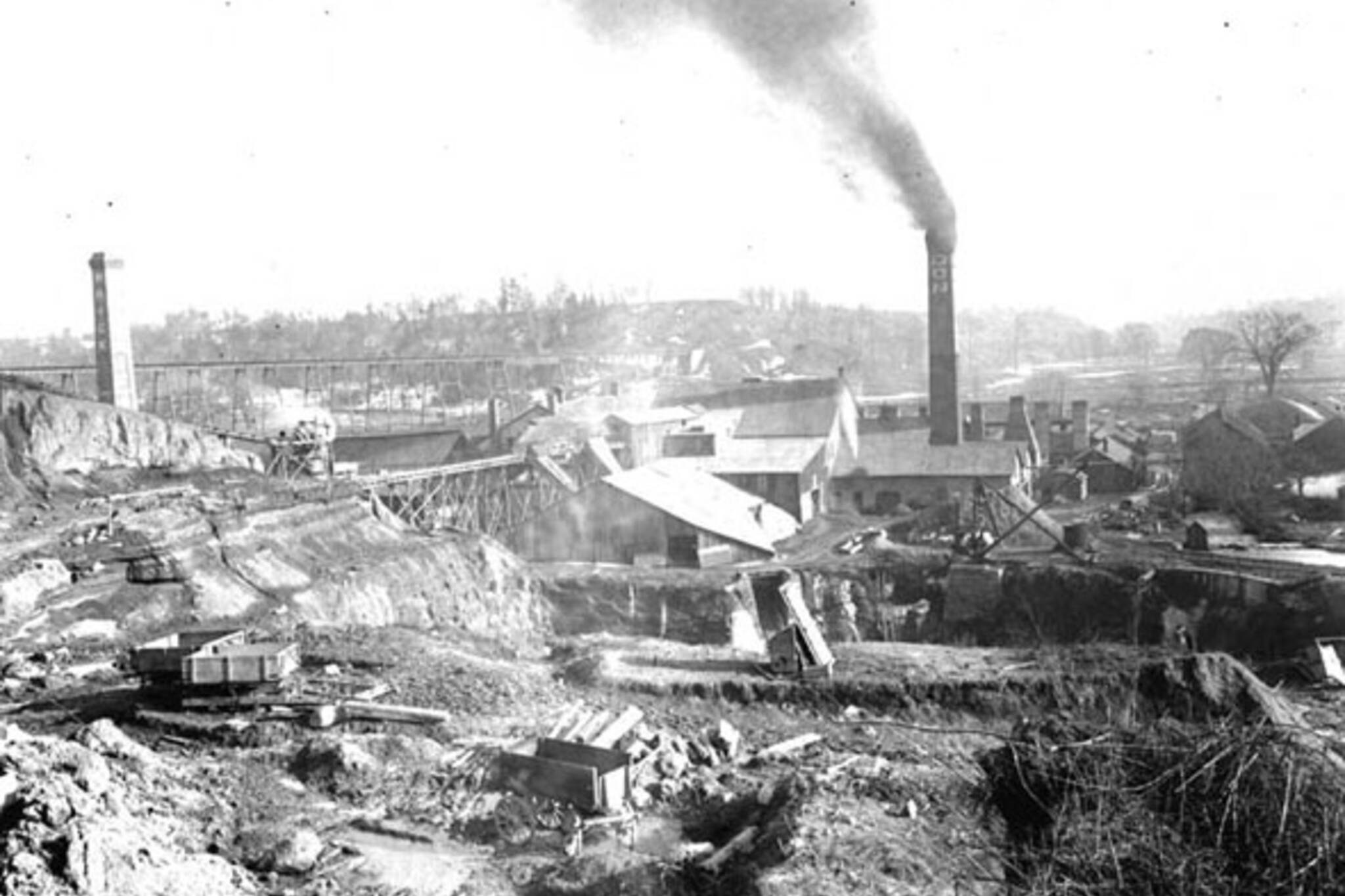

Production steadily ramped up in the early part of the 20th century, partly in response to the destruction caused by the great Toronto fire of 1904 and the new laws that followed prohibiting the use of combustible construction materials.

By 1907, the packed kilns were turning out 85,000 to 100,000 bricks each day. Once cooled, the building material was loaded onto rail cars or carted out of the valley using Pottery Road. Around this time the "valley" chimney, the only one still standing, was constructed to vent one of the kilns.

The company changed hands several more times and production eventually reached a peak of 25 million bricks a year. In the 1920s, Geologist A.P. Coleman used the walls of the excavated pits and fossils gathered by workers to help trace much of the area's glacial history through the various layers of rock, producing his book Ice Ages, Recent and Modern in 1926. In the second world war, the factory employed prisoners of war housed at nearby Todmorden Mills.

Hurricane Hazel in 1954, specifically its aftermath, was a defining moment in the history of the Don Valley Brick Works. To improve safety in the wake of the deadly flooding, the Metropolitan and Toronto Region Conservation Authority acquired the city's ravine lands including the area around the quarry and kiln site. Despite a post-war boom, the brick works fell into decline and finally closed in 1984.

The disused site was first earmarked for residential use but the land was expropriated in 1987 because of its position on the Don River floodplain. Unfortunately for the MTRCA, the residential designation pushed up the value of the land significantly. Over the next few years, the gaping quarries were gradually filled in using material excavated from the foundations of Scotia Plaza and landscaped ponds were created in their place.

In 2010, after decades of dereliction, Evergreen, a Canadian non-profit organization that aims to connect nature and people, took stewardship of the site and renovated many of its historic features. As a reminder of the past, bricks still litter the surrounding hillside.

Photos: City of Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments