Nostalgia Tripping: The Great Depression in Toronto

The Great Depression in Toronto is perhaps best explored -- in fictional terms, at least -- by Hugh Garner in his classic novel, Cabbagetown. It's semi-autobiographical, as Garner included some of his own life experiences of the 1930s. He lived on Wascana Avenue, in the area he describes as Cabbagetown, now Regent Park and part of Corktown, then a primarily working-class neighbourhood. His work is one of the most enduring portrayals of that decade in Canadian literature, and the upcoming anniversary of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 led me to think again about Garner and the 1930s in Toronto's history.

At the start of the Great Depression, Ken Tilling, the protagonist, is sixteen years of age, having left high school seven months earlier in order to find a job. His struggles throughout the 1930s, marked by brief periods of unrewarding employment, the eventual "riding the rails," and, of course, lack of work, coupled with difficult circumstances in his life, are characteristic of many experiences of working-class males during the years following the financial crisis.

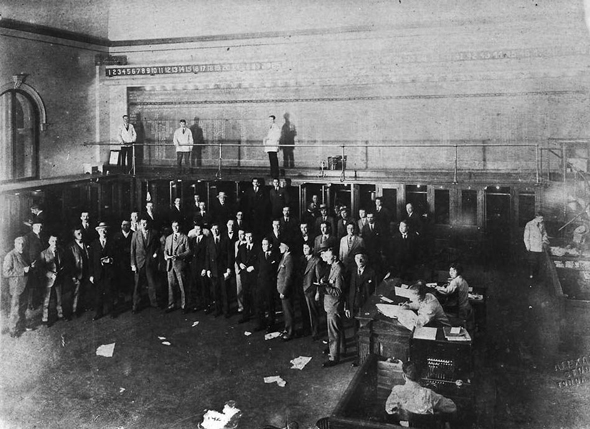

In Toronto Since 1918: An Illustrated History, James Lemon provides some gruelling statistics from the 1930s: in 1931, 17% of Torontonians were unemployed. Two years later, the census reported that 30% were not able to find work, and in 1935, 25% of the population in Toronto and the suburbs were on relief.

Single unskilled drifters, like Ken, were the worst affected by the Depression. For Cabbagetowners, the factories located close to their neighbourhood, such as Heintzman & Co., were the main sources of employment. One of the reasons for high unemployment among the unskilled workers was due to the fact that the value of products fell by half in 1933. The same year, wages dropped to 60% of their levels in 1929.

Women employed at garment production factories like Eaton's, for example, were paid per each article they made, at the rate of $12.50 a week, as the minimum wage was established in the 1920s. They were forced to work faster, and their pace was measured by stop watches. They would be fired for failing to reach the expected production level.

At the same time, the 1930s offered better employment opportunities for women then previous decades, as Katrina Srigley suggests in her book, Breadwinning Daughters: Young Working Women in a Depression Era City, 1929-1939. Although they often worked in female-dominated occupations, as servants, secretaries, factory workers, teachers, and nurses, in many families women became the primary breadwinners. Despite such high expectations of them, they often enjoyed their sense of independence and of economic responsibility.

Construction slowed down drastically. After 1931, no commercial or industrial building were erected. One notable example, Eaton's College Street (now known as College Park), was originally planned as a 38-storey skyscraper, but the new reality scaled down the project. Only residential construction was flourishing, even though not a significant number of new houses were built. In the late 1930s, numerous apartment buildings were constructed, with the effect that by 1940 there were 60% more units than in the start of the 1930s.

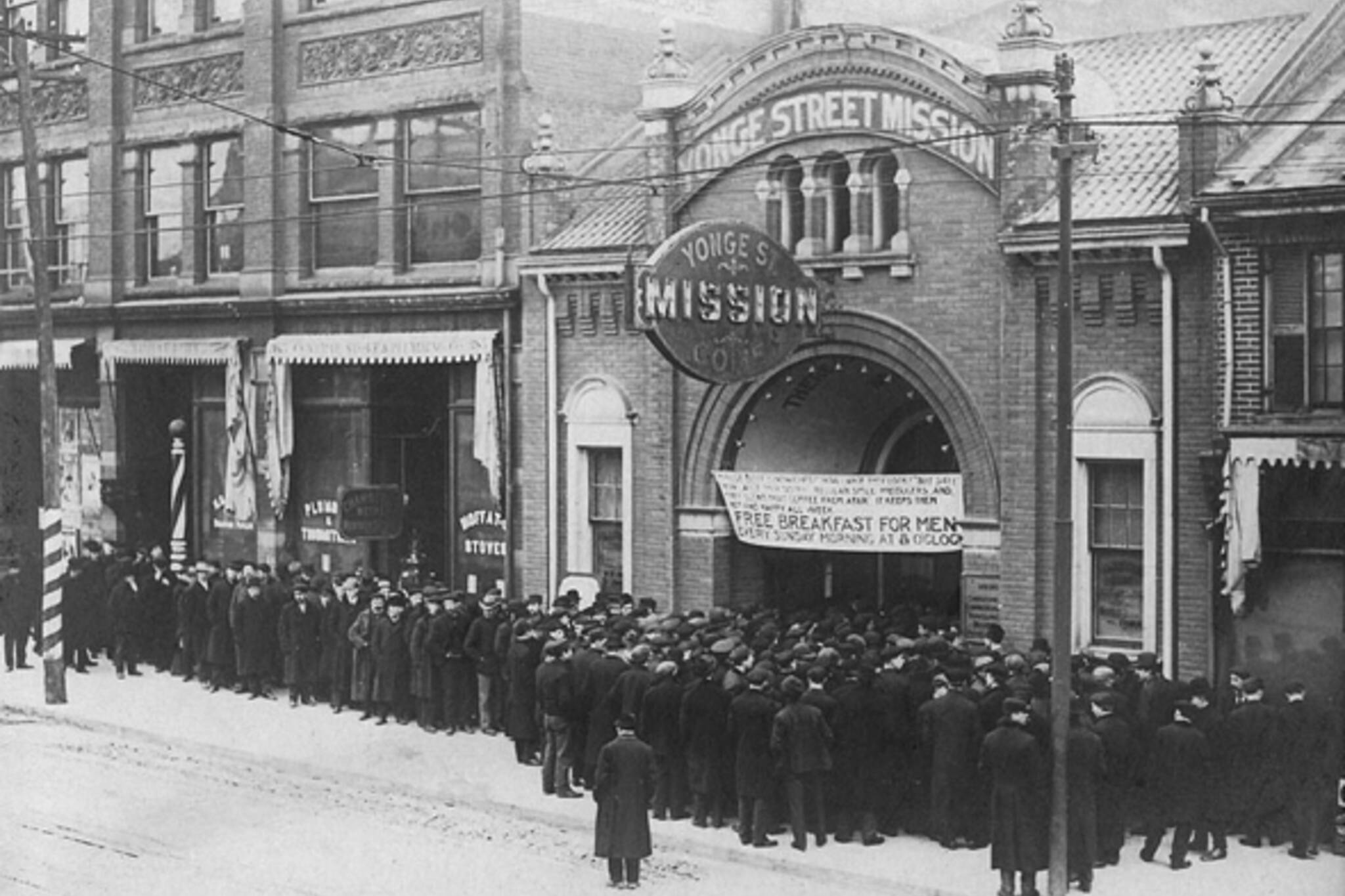

To prevent further unemployment, the city created the Civic Employment Office and Central Bureau for Unemployment Relief in 1930, and in 1932, the newly established Public Welfare Department was finding jobs for the unemployed through relief work.

The costs of the Depression were personal as well. As Garner relates, many men, as the main providers in their families, felt ashamed for not being able to support their wives and children, which often led to conflicts between the spouses. Children born to unmarried women were also a source of arguments, and the author states, many young people indulged in one another simply because they had nothing else to do.

Housing became a problematic issue, and young people delayed leaving their family home. The number of marriages fell by 40%, and the birth rate along with it. The roots of the urban renewal scheme in Cabbagetown, of which 90% was razed to the ground and rechristened as Regent Park Housing Project in the 1950s, can be traced to the 1930s concerns over slum conditions in Garner's neighbourhood. The Bruce Report, authored by Harry Cassidy and Eric Arthur, two social reformers, exposed the deplorable conditions in which 2,000 families lived. They proposed to replace the existing housing stock with publicly funded housing, based on the garden city model. This proposal failed, but the city helped to finance renovations in some of the homes between 1936 and 1939.

Anti-Semitism was on the rise during the decade in Toronto. On August 16, 1933, an event regarded as the most violent ethnic clash in the history of the city took place in Christie Pitts, then known as Willowvale Park, following a playoff game for the Toronto junior softball championship. Nobody was killed, but a fight involving baseball bats and irons bars, lasted five hours, taking over the neighbouring streets. A plaque commemorating the event was placed in the park by Heritage Toronto in 2008, seventy-five years after the riot.

Images from the Wikimedia Commons.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments