The Gutting of the Canary Reveals Its Past, but Can it Survive the Wrath of the Pan Am Games?

It's been almost three years since the Canary served its last open-faced turkey sandwich. Sadly, the much-photographed sign is gone, but rumours that there was something going on behind the closed blinds at the Cherry Street landmark have revealed a fascinating moment in the history of the building.

As layers of history have been peeled back, the survival of the building itself has become dubious.

I arrived before noon to find Ken - he wouldn't give his last name - working amidst the dust and chaos of the greasy spoon's dining room, which has been gutted to the walls, with only the short order kitchen still intact, and divots on the floor where the stools and the lunch counter once stood. Ken's been living in the building for two years, but has had friends and family here for over twenty - a revolving community of artists, many of them employed in the film industry that gave the Canary its last gust of business after the industries that once surrounded the building evaporated in the '70s and '80s.

The Canary's counter and soda fountain have been on a curious journey back to where they started 50 years ago. Juxta Productions, a building tenant, are behind the pop-up store at Queen and McCaul which has been publicizing movies like the latest Harry Potter and Daybreakers, the vampire thriller for which Ken and Juxta built a bloodsucker diner using the Canary's fixtures. Ironically, it was just up the street, near Dundas and University, where the Canary restaurant operated for five years before moving out to the industrial bustle of Cherry and Front in 1965, where members of the same family ran it until it closed in 2007, a victim of the closure of the Bayview Extension and the long development limbo of the Donlands.

The space was in bad shape when Ken and his fellow tenants got permission from Ontario Realty Corporation, the building's owners, to clean it up for use as a film location and event space late last year. "It was pretty decrepit," he says. "I wouldn't have eaten here - it was pretty bad." Worst of all was the hundred or so paint cans full of congealed kitchen grease they found in a back room, which they cleaned up prior to gutting the space and opening up windows and doorways long boarded over.

What they've revealed is the ghost of the building's former tenants. There's not much left of the Palace Street Schoolhouse, the second oldest in the city, and just a storey tall when it opened in the 1850s. By the 1890s, however, it had become a turreted and gabled Victorian hotel - the Irvine House and then the Cherry Street Hotel, and that building has emerged again under Ken's care. The Canary dining room was probably its tavern, and the space next door, which housed the diner's storerooms and walk-in fridge, was a sun-filled lobby, complete with a room-sized safe behind the check-in desk.

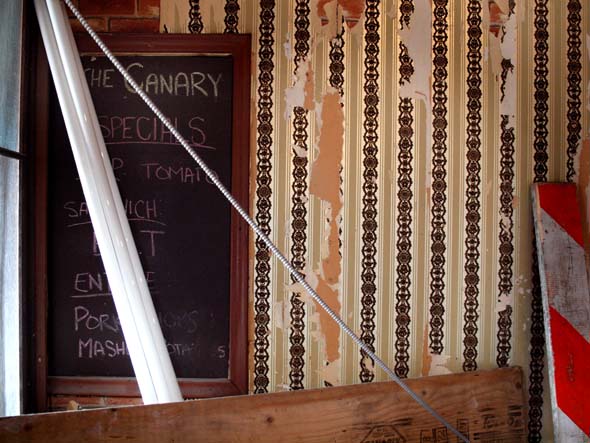

Ken has uncovered layers of wallpaper and murals, and traces of flowers stencilled onto the walls. A blackboard by the door still advertises the specials on the Canary's last day, but a grander space is emerging from the dust and grime. The building can still be glimpsed on architect's drawings for the Pan Am Games athlete's village, part of a grand entranceway, but the tenants have heard that the ORC and the Pan Am organizers have plans to tear down everything but the faรงade - "and wipe out 150 years of Toronto history," says Ken, noting that everyone is on a 2-year lease. "They have plans but they don't tell you very much. They're only putting band-aids on these buildings - they said they spent a million on the brickwork and new slate roof, which might be true."

Ken says they're hoping that their rehab of the space will give people a sense of the building's evocative qualities, and discourage Waterfront Toronto and the Pan Am organizers from gutting all that history away. "Maybe you can help us out," he asks as I take pictures. "Do you know anyone who needs a really nice party space?"

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments