That time Toronto got its first taste of the LCBO

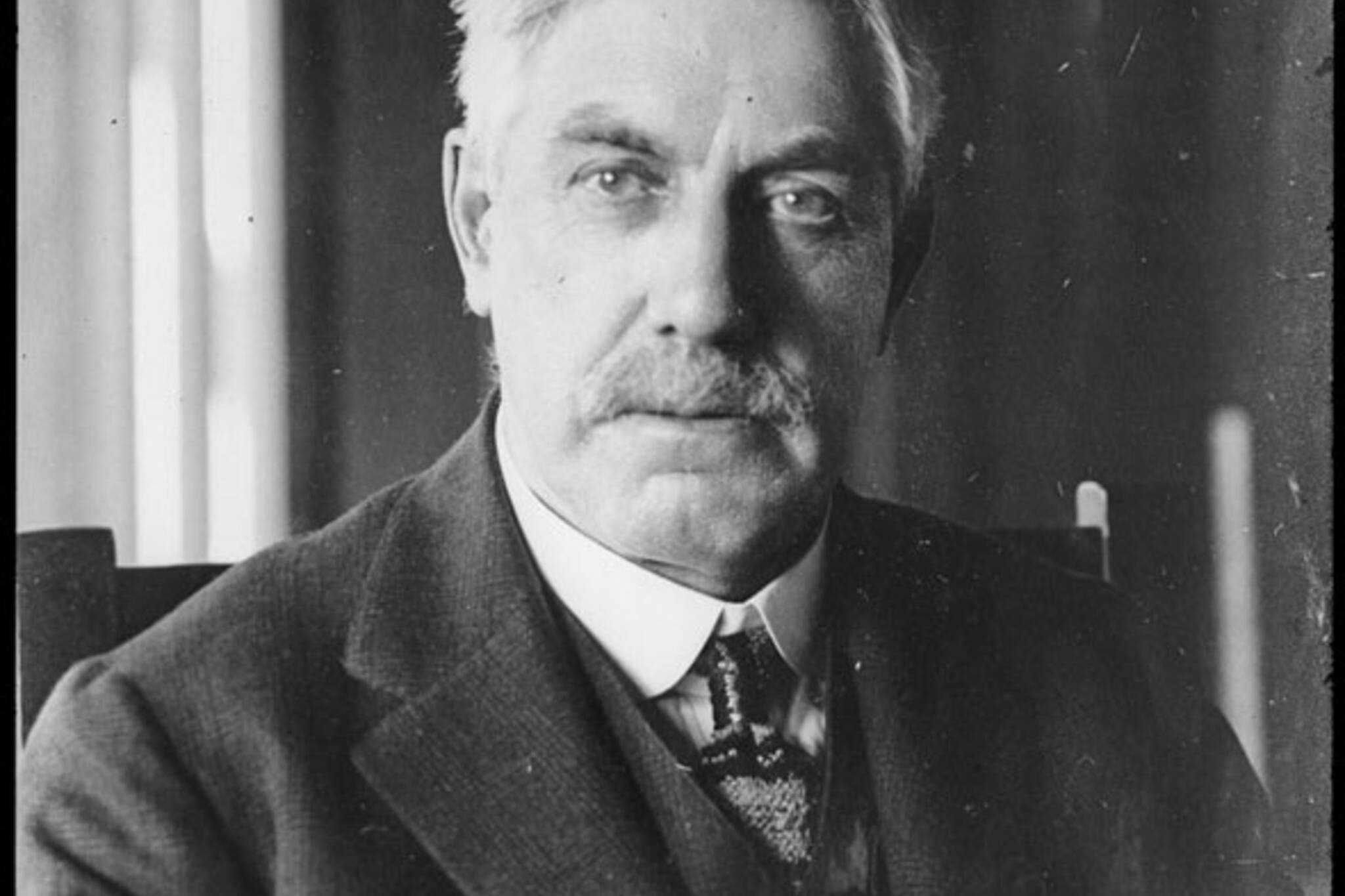

David Blythe Hanna was confident the big day would go off without a hitch. As the first chairman of the newly-established Liquor Control Board of Ontario, the former railway manager was charged with making sure the province's loosened licensing laws would be followed to the letter. June 1, 1927 was to be the first day of public alcohol sales since the start of prohibition 11 years earlier. Before that, alcohol was dispensed by prescription only.

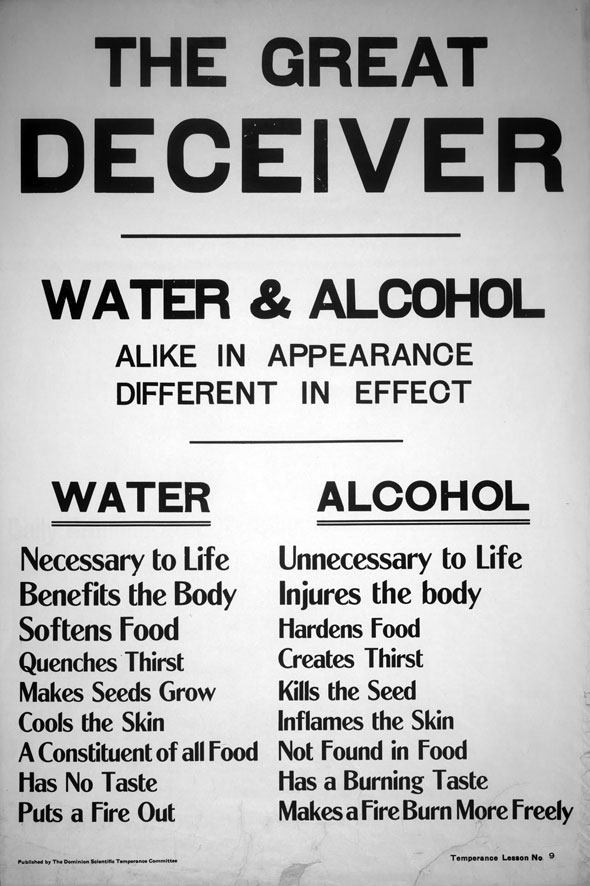

In 1916, Ontario partially nixed the sale of alcohol, partly as a wartime austerity measure. The Temperance movement became all-out prohibition when the restrictions were beefed up in the 1920s. Inevitably, bootleggers from the United States ran liquor across Lake Ontario and the Detroit River, sometimes in the false bottoms of small boats, to underground bars and blind tigers.

Notorious gangster Rocco Perri was one Ontario's bootlegging kingpins. Based out of Hamilton, the Italian immigrant rose to prominence off the back of a series of brazen smuggling missions in the mid-1920s. The self-described "King of the Bootleggers" saw himself as a sort of Robin Hood character, delivering alcohol to a thirsty province subdued by unfair rules.

"It is an unjust law. I have a right to violate it if I can get away with it," he told the Toronto Star in sensational 1924 interview. "Men do it in what you call legitimate business until they get caught. I shall do it in my business until I get caught. Am I a criminal because I violate a law that the people do not want?"

On the other side, The Globe was a supporter of the Ontario Temperance Act, the legislation keeping the province dry. "With all its faults, the [act] was a step in the right direction of eliminating the evils that have been associated with the liquor traffic and developing a generation of sober, temperate people," read an editorial on the eve of birth of the LCBO. "Government control makes for the breakdown of sobriety, aids drunkenness, and provides easy facilities for the obtaining an abundance of liquor."

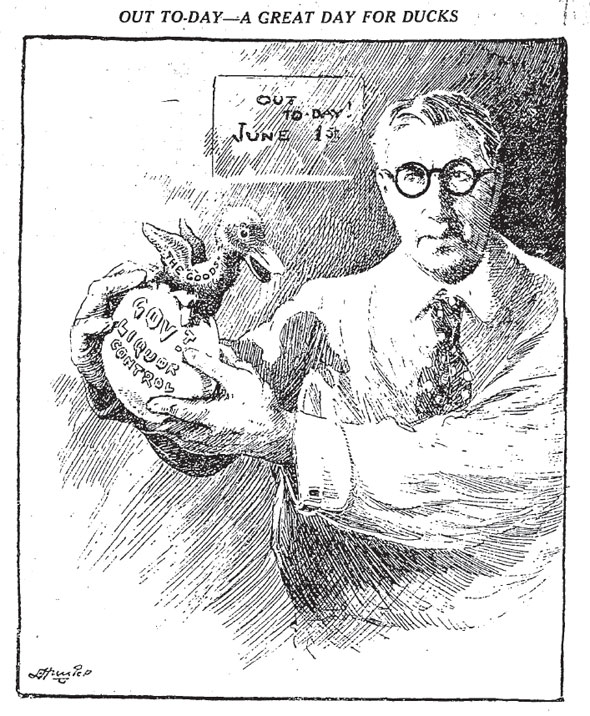

But the majority of people in Ontario appeared happy for prohibition to end up on the scrap heap. In 1927, the LCBO, the government body charged with ensuring no-one had much fun as a result of the new rules, set up its first 12 stores, six of them in Toronto, and established the process by which liquor would henceforth dispensed.

On the morning of the first day of sales, hundreds of people queued outside the Toronto stores, hours ahead of the official opening time at 10:00 a.m. Some women brought empty strollers to use as shopping carts and, despite long waits, "there was very little jostling," according to the Globe. Some people showed up in taxicabs, others in limousines.

Procuring a tipple quickly proved a bureaucratic nightmare. Anyone wanting, say, a case of O'Keefe's Special Half and Half -- an "extra mild blend of O'Keefe's Special Ale and Special Stout for smoothness and flavor unequaled" -- would first have to apply for a license at the liquor store or at a dedicated outpost on King St. In Toronto, the store locations were: 1271 Dundas St. W., 154 Wellington St. West, Church and Lombard, 170 Danforth Ave., 1271 Queen Street West in Parkdale, and Queen and Woodbine in the Beach.

The crowd around the licensing window was tight, The Star wrote. "One had to be a contortionist to get one arm free to write out a slip." Once furnished with a license to buy alcohol, customers were allowed to proceed to the store proper, where there was a team of censors who checked and vetted paperwork. A pink slip had to be completed for delivery orders or a white slip for "cash and carry."

For reasons that weren't made clear, differing brands were not permitted on the same form. "This is absolutely the worst system I have ever seen," said one customer. "Me for the bootleggers," said another, departing. "where you can get fast service."

"Getting through Uncle Sam's immigration turnstiles was child's play compared with running this gauntlet," The Star wrote. "The crowd of purchasers moved as slowly as a great mogul engine being derricked out of a ditch."

D. B. Hanna's LCBO set strict limits on the amount each person could carry out. No more than a single six pack of beer was permitted to leave the store in the hands of a member of the public and mixing types of alcohol was also banned: no whiskey and wine on the same visit. Delivery was mandatory on larger orders, at a fee of 30-cents.

No "repeating," placing two large orders on successive days. Cash only.

"The purchase of the liquor required much ingenuity and patience," The Star said. Many left empty-handed.

Though permits had been available a week in advance, few people had claimed one, and lines moved slowly. The Star reported that 1,070 had been served as of 2:00 pm on the first afternoon across all of Toronto. The biggest purchase of the day was for "an assortment of wines and spirits" at the Dundas store. The bill was $68.50--close to $1,000 in today's money.

Customers unfamiliar with the complex ordering procedure scattered spoiled pink and white slips on the floor and tempers occasionally flared, especially when it came close to closing time. There were 200 people still waiting in line when the central store at Church and Lombard closed at 9:30, and police were called to escort the crowd away.

Hanna blamed the lack of organization on the public: the drinkers of Toronto should have applied for their permits in advance. "It was the people that came [to the stores] for their permits who caused the congestion," he said. Critics also bemoaned the narrow selection in the small stores.

The Toronto Star put it poetically: "Mr. Hanna can now appreciate the truth of the saying that the best laid plans gang aft agley. If he aimed at dignity he got a scramble and confusion and made many as they abandoned the hunt exclaim that after all prohibition was better than no liquor at all."

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: "D. B. Hanna, Ontario Liquor Commission," Feb 8. 1927, Globe and Mail fonds, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1266, Item 9936; "The great deceiver: water & alcohol alike in appearance, different is effect," 192-, Dominion Scientific Temperance Committee, Toronto Public Library, Item 9. M; "Out To-Day--A Great Day for Ducks," June 1 1927, Toronto Star.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments