That time Toronto had a system of pneumatic mail tubes

For Toronto's tireless city hall reporters, filing copy is quicker and easier than ever thanks to the Internet: write directly into a special web application, paste text into an email - both reach editors in seconds.

For the Toronto Star in 1930, however, filing a story from its bureau at Old City Hall took considerably longer. A draft dashed off on a battered Smith Corona typewriter would be handed to a copy boy who would sprint from the press gallery, down Bay Street, and over to the paper's towering art deco headquarters on King West.

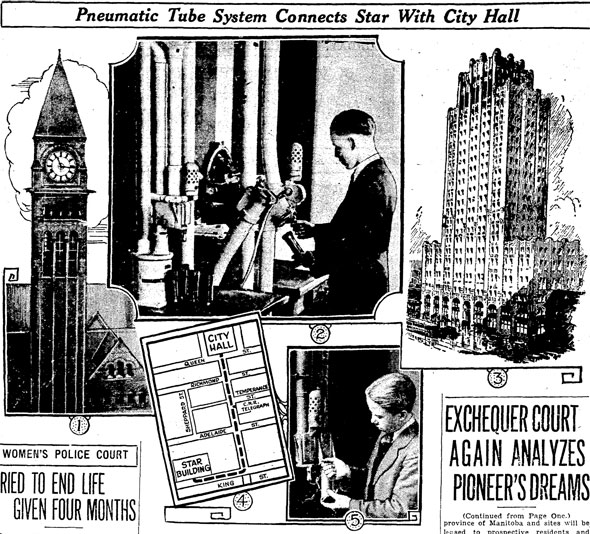

Then the paper did something that would change all that; it teamed up with the Toronto Telegram to install a system of pneumatic tubes under Bay Street capable of sucking a sealed canister from the press room of Old City Hall - then home to courts, police headquarters, and the offices of aldermen - to either paper's headquarters in 70 seconds. Sending a reply was just as fast.

It was the first time in North America that newspapers were directly linked with a beat via tube.

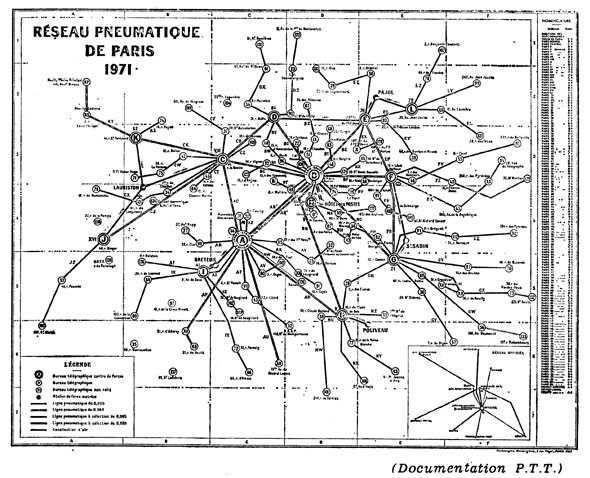

The system, while novel and exciting for the Star and Telegram, was far from new. Paris' Poste Pneumatique, the most extensive such system in the world at its peak, blasted letters, telegrams, and other physical media through more then 400 kms of pressurized pipes beneath the city's streets. By 1919, it handled around 12 million pieces of mail.

The network was installed on the inside of sewer pipes and linked the city's various sub post offices. To send a piece of mail, a perfumed note to a sweetheart, say, all one had to do was pay the postage and hand it off to the local "tubiste."

The precious cargo would be sealed inside a cylindrical canister and dropped in the end of the correct pneumatic tube. The result was similar to vacuuming something large off a carpet. The pressure of the tubes, generated by a giant central steam plant, would suck the canister at speeds approaching 30 km/h to its destination. Well, most of the time.

As architectural historian Molly Wright Steenson recalls in the excellent 99% Invisible podcast on pneumatic tubes, Paris' tubiste's would fire a gun into a blocked pipe and use the resulting echo to locate an obstruction.

Practically every major city had a similar system. Even Toronto had one.

In April 1904, Sir William Mulock, a prominent lawyer, businessman, and postmaster-general, wrote to the Toronto's board of control offering to lay a network of iron tubes connecting the city's post offices with a new central distribution office to be built near Old Union Station, if the federal government could be convinced the chip in the cash.

"Owing to the peculiar local difficulties in securing rapidity of despatch of the Toronto mails between all parts and the Union station, I have come to the conclusion that these difficulties cannot be overcome by vehicles or streetcar service and the only solution, it seems to me, is the Pneumatic Tube System," he wrote, recommending a site behind the customs house on York Street.

Mail would come off trains, be quickly sorted, and delivered to the appropriate sub post office by mail tube where postal workers would be waiting to deliver it, Mayor Thomas Urquhart said.

It was an ambitious plan but one with almost universal support. A company in Glasgow had started making the pipes when, later that year, the great fire of Toronto destroyed a swath of downtown buildings, leaving prime real estate east of Old Union Station on the south side of Front Street up for grabs.

The Grand Trunk Railroad wanted to build a new, larger Union station between York and Bay, which by now was the city's preferred site for its pneumatic mail depot. Canadian Pacific wanted part of the action too, and the three squabbled about who should claim the vacant land. In the end, the railways built the current Union Station and the high-tech pneumatic post office idea faded.

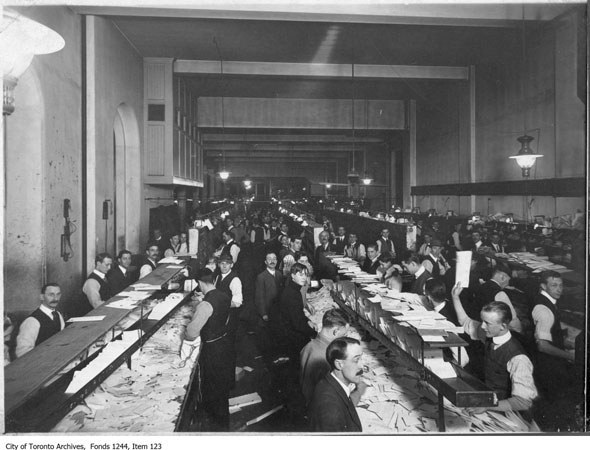

But that wasn't the end of tube mail in Toronto. Eaton's and other large businesses like the Royal York Hotel and the Toronto Star had internal systems, staffed by teams of dedicated operators, for sending paperwork between departments.

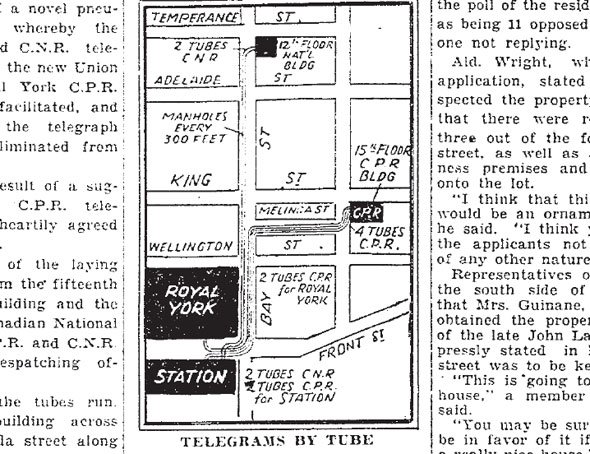

In a rare show of co-operation in 1928, Canadian Pacific and Canadian Nation Railways laid what would become the foundation of the Toronto Star and Telegram system by running an elaborate 4,500-metre pneumatic tube network from their respective transmitting offices - at Yonge and Melinda and Bay and Temperance - down Bay to Postal Station A at Union Station. A small spur connected to the mail room at the Royal York Hotel.

Each property had two tubes: one for receiving and another for sending. The Royal York was connected to the CP building, CP and CNR were connected to the station post office but not to each other. Manholes every 300 feet down Bay provided access to the 2 1/4-inch copper tubes - which were laid on a concrete foundation and encased in creosoted wood - in case a canister became stuck.

It took almost a full minute for the eight-inch fibre containers to travel from the 15th floor of the CP building, down to the street, under Bay, to the mail room at Union Station. A special percussive buffer attached to the front of the canister absorbed the shock of delivery. Similar systems were in use in Montreal and Winnipeg, but this small network was the biggest in Canada.

Two years later, the Star and Telegram joined the pneumatic mail system, installing two sets of pipe in parallel down Bay Street. At its extent, the system included 7 properties, though there was no central exchange and most were only connected to one other place.

It's not clear when the pneumatic tubes fell into disuse. The Royal York still has the transparent pipes of its internal system on display but, sadly, its staff have found more convenient (though infinitely less exciting) ways of getting messages through the giant old building.

Of all the properties that were ever connected to the pneumatic mail system, the Royal York, Old City Hall, and Union Station are the only ones still standing. No-one working in any of the buildings knows anything about the old network. Presumably much of it would have been destroyed when the TTC excavated Union subway station under Front Street in 1949.

In later times, Robarts library opened with a pneumatic tube system, NASA's Houston mission control centre had one, and the devices were briefly in vogue with banks before fully automatic ATMs.

The Bay and Front branch of Royal Bank introduced the first "Television Banking" terminal in 1976. Users would walk up, press a button, and be connected to a teller in a secure part of the building via a closed circuit camera. The transaction would be carried out via pneumatic tube and loudspeaker, with checks and cash dropped into the whooshing pipe. A telephone receiver was available for sensitive matters.

"You don't feel cut off from the customers even though you're only watching them on TV," said Anna Sauve, one of the tellers. One of the first users, 62-year-old Saul Shapiro of Bathurst Street was less than impressed: "big deal," he said when the Star asked him what he thought of the new technology.

Pneumatic banking worked better in the suburbs where drivers could pull up to a special terminal and transact business from their seats. Several of these systems lingered in to the 1980s and beyond.

Amazingly, the biggest system of them all, the underground air mail system in Paris, would last until 1984. In Toronto, tube mail is now largely confined to supermarkets.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Image: Toronto Star Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments