A brief history of Small's Pond, used then abused

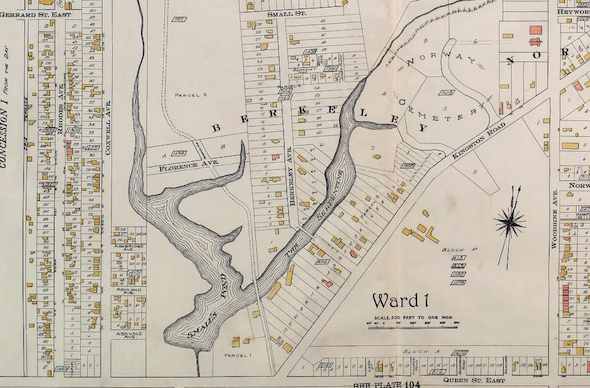

No collection of lost waterways of Toronto would be complete without a trip to the east end of the city and the intersection of Queen and Kingston Road - the location of Small's Pond. The word "pond" actually understates the size of this lost body of water - it was once roughly 12-feet deep in the middle and stretched in two fingers roughy 40-feet wide that ran parallel to Coxwell Avenue and Kingston Road, forming a rough U-shape.

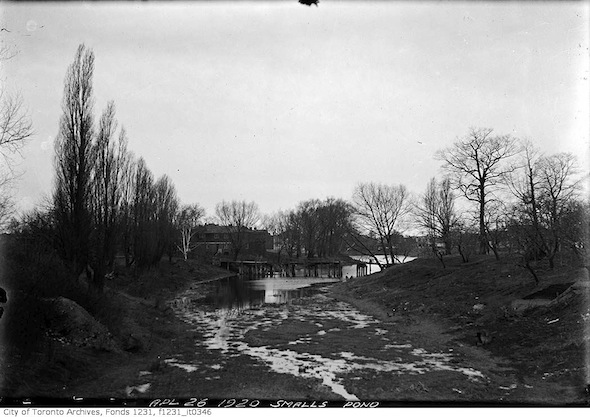

The Kingston Road finger, named The Serpentine, was popular with ice skaters in winter and recreational boaters in the summer. In the early part of the last century, during times of shortage, workmen would chisel away at the frozen plane of the lake to secure precious clean ice for sale in the city. Other bodies of water like the Don were too polluted to use for ice - and before long Small's Pond would be the same way.

Fed by three streams, Small's Pond was a natural feature of the landscape north of Queen Street, just above Lake Ontario. The largest of the pond's tributaries, Small's Creek, flowed from the north into the western finger of the U-shaped pond and likely provided much of its water. The creek is still visible certain times of year in Williamson Park ravine north of Gerrard Street and it is responsible for the broad dip that winds south from the Danforth roughly alongside Coxwell Avenue.

Tomlin's Creek, the other river that flowed into the pond, rose just north of Kingston Road at Glen Davis Crescent. Roughly following the curving road south it passed over Love Crescent and Woodbine Avenue, through St. John's Norway Cemetery before connecting with The Serpentine just north of where Dundas Street terminates today. The last, relatively minor tributary entered the pond just east of Small's Creek. It too flowed south a short distance from Cairns Avenue.

Despite its popularity as a destination for local children, Small's Pond saw its fair share of tragedy and close calls. In August 1919, John Vice, a nine-year-old boy, drowned after falling out of an old boat occupied by several other children in the deepest, reed-choked section of the water. His body was recovered later that night. The Toronto World cited the depth of the water and thick weeds as contributing factors in the tragedy.

In 1920, a man the press referred to as Brother R. Chalmers was commended for rescuing two small boys from drowning in the pond. Returning from a funeral, Chalmers discovered the boys in difficulty, swam out to the pair and pulled them to shore. For his heroism, he was awarded a medal from the Royal Humane Society.

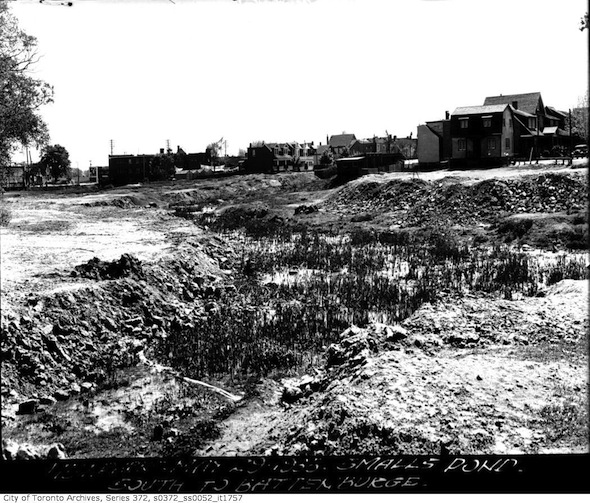

By the 1920s Small's Pond had become polluted and stagnant due to its tributaries being routed underground into sewers, away from the pond. "Obnoxious odours" blown on the breeze during hot weather bothered residents of Kingston and Edgewood Roads enough for stories to begin appearing in the city's newspapers around at the time.

After several years of wrangling, the pond was eventually drained and filled with earth around 1935. All that's left now is a few winding roads and deviations in the land. Some of the land once occupied by the Pond and its tributaries are preserved as parkland and still enjoyable today. Next time you're in the neighbourhood, be sure to check out the small park south of Dundas Street just west of Kingston Road - there are several signs of the old pond.

FURTHER READING:

- That time when the Don River was straightened

- A brief history of Castle Frank Brook, the ravine carver

- A brief history of Taddle Creek, Toronto's lost treasure

- A brief history of Garrison Creek, lost but not forgotten

MORE IMAGES:

Small's Pond looking south

Small's Pond bridge

Smalls Pond bridge with low water level

Alternative view of the drained pond

References: Lost Rivers of the Beach - Beaches Living Guide; Toronto World - Oct 10, 1912; Apr 18, 1914; Aug 16, 1914; Oct 16, 1915; Aug 23, 1918; Aug 10, 1920; Aug 12, 1920; Toronto Daily Mail - Jan 2, 1893

Photos: Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments