The strange tale of the Toronto Stork Derby

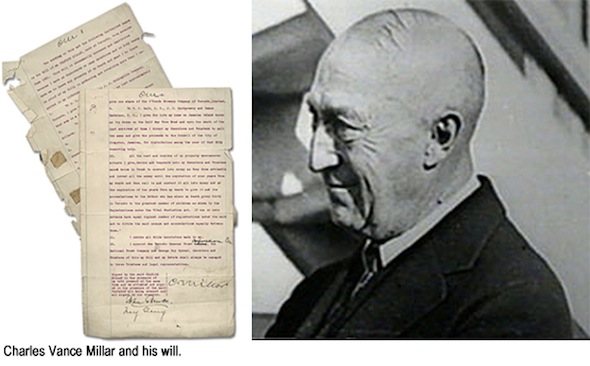

On October 31, 1926, Charles Vance Millar, an eccentric Toronto lawyer, businessman and all-round prankster, gasped his final breath at the top of a steep flight of stairs, clutching his chest in agony as he suffered a fatal heart attack. Millar's coronary marked the beginning of a bizarre legacy that put bitter enemies at war, caused moral conflict and ultimately brought several children into the world.

Born in 1853 in Aylmer, Ontario, a small town southeast of London, Millar studied at the University of Toronto and, after graduating with exemplary grades, pursued a career in law. Millar passed the bar exam, opened his own practice and began a life-long career as a legal advisor.

A shrewd businessman, Millar and a group of fellow layers purchased the British Columbia Express Company, formerly Barnard's Express, in 1897 and were able to profit from mail delivery in the Prince George region via the newly constructed Grand Truck Pacific Railway.

Away from work, the popular lawyer developed a reputation as a dedicated practical joker who loved to exploit greed and see people jump through hoops for financial reward. One of Millar's favourite pranks was to leave a $1 bill on the street and watch from a distance as the lucky recipient surreptitiously pocketed the cash.

It didn't come as much surprise to his friends, then, when Millar's will was packed with unusual requests for his estate. Millar left $700,000 of Catholic O'Keefe brewery stock, which it later turned out he didn't actually own, to seven Protestent ministers and temperance advocates under the condition they were active in the business.

Other clauses awarded $2,500 of coveted Ontario Jockey Club stock to three anti-racing campaigners and awarded joint tenancy of Millar's Jamaican holiday home to a group of bitterly rivaled lawyers.

Most peculiar of all was his stipulation that the remainder of his estate be converted into cash and awarded to the married Toronto woman who gave birth to the most children over the next decade. In the event of a tie, the money was to be divided equally among the winners. What started out as a substantial $500,000 fund skyrocketed when stock Millar held in the Detroit-Windsor tunnel project increased considerably in value.

Dubbed the Stork Derby by the media, the strange contest quickly became national and international news. Attempts by the Supreme Court of Canada to invalidate the will proved unsuccessful, mainly due to the document's meticulous preparation, and excited copywriters began to feverishly speculate about who might claim the cash.

Perhaps not surprisingly for the Depression era, many of the women vying for the prize money were from low income families — during the first few years there were so many people with a legitimate claim to Millar's money it was difficult to identify a core group of contenders.

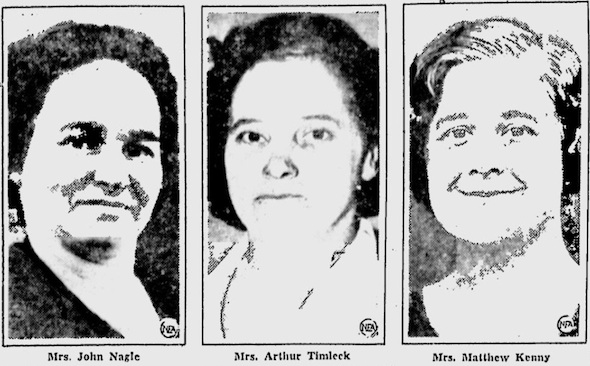

Years later, as the diapers began to accumulate and the truly prolific baby-makers pulled ahead of the pack, several women seemed likely to pocket all or at least part of the money. Alice Timleck, Kathleen Nagle, Annie Smith, Isobel MacLean and Lillian Kenny all had multiple, registered children during the contest and many more outside it.

Kenny, unlike the other contestants, told newspapers she planned to pocket the entire sum should she eventually win outright. Her family had lived in poverty since her husband, Matthew Kenny, had been let go from his job at a tire factory.

The other mothers had similar stories, though Kathleen Nagle was honest enough to admit the prize money had spurred her and her husband to produce more offspring. "I'd like to be the mother of the biggest family in Canada" she told The Grape Belt and Chautauqua Farmer, a New York newspaper, in 1936.

Alice Timleck believed she was most likely to come away with the money because all of her children were properly registered, a key requirement of the Stork Derby. Despite having 17 children in her lifetime, Timleck believed contraception was "wonderful."

When the decade was out and the contest closed, lawyers went to work on the case for the next 17 months trying decide the winners. In the end four women — Alice Timleck, Kathleen Nagle, Annie Smith and Isobel MacLean — all mothers to nine Stork Derby children, walked away with $125,000 each.

Lillian Kenny and another woman, Pauline Mae Clarke, received a consolation prize of $12,500 for their kids. Several of Kenny's qualifying children died shortly after birth; in Clarke's case, more than one of her brood had been born outside of marriage, which went against Millar's rules. The remainder of the Stork Derby money covered lawyers fees and a substantial donation to a children's charity.

The competition got the TV movie treatment in 2002 with the release of The Stork Derby based on the book Bearing the Burden: The Great Toronto Stork Derby 1926-1938 by Elizabeth Wilton. The picture also tells the story of Grace Bagnato, a mother disqualified from the contest for her marriage to an illegal Italian immigrant and lack of registration papers for several of her 12 living children, nine who were born during the contest.

64 years later, it's easy to see the light side of the Stork Derby, but it's worth noting the contest caused some of the women and children involved plenty of distress. Millar might have had only the best intentions — ultimately we will never know - but his final practical joke certainly had the desired effect of showing how far people were willing to in the Depression for money.

The only clue Millar ever left to his motivation appeared in the tenth clause of his will, the section after the baby contest, where he called his estate and the baby prize "proof of my folly in gathering and retaining more than I required in my lifetime."

Lillian Kenny's children (lead image) and street portraits of Lillian Kenny and Pauline Mae Clarke from Spaarnestad Photo. Newspaper portraits of Kathleen Nagle, Alice Timleck and Lillian Kenny from The Grape Belt and Chautauqua Farmer, October 23, 1936. Charles Vance Millar's will image from the Archives of Ontario. Lillian Kenny's family portrait from the The Telegraph-Herald, October 24, 1937.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments