Dear Giorgio, my Toronto includes graffiti

In his latest promise to "get tough" on Toronto's criminal element, mayoral candidate Giorgio Mammoliti has indicated that he'll support councillor Sandra Bussin's (Ward 32, Beaches) plan to ban the sale of spray paint to those under the age of 18. Well, perhaps "support" isn't quite the right word. What Mammoliti wants to do is institute a more draconian plan that would see first time offenders fined $5000 for spreading graffiti or tagging buildings. He'd also like to shift responsibility away from the retailers and onto the parents for such offences, as is demonstrated by his desire to see both the perpetrator and his/her legal guardian serve community service in the wake of a graffiti conviction.

I suppose the desire of municipal politicians to curb the spread of graffiti is nothing new. But, bans like this fail to register the complex nature of the relationship between a city and its graffiti.

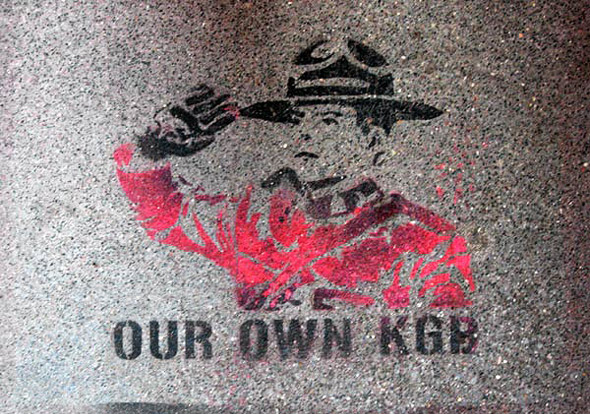

So, let's get two disclaimers out of the way from the outset: I generally like graffiti, and I think that much of it enriches the urban environment. There is something quite intriguing and rewarding about stumbling upon a freshly painted mural or a particularly intricate tag. Spaces that might once have been drab, artless and institutional are often reinvigorated by the presence of unsolicited art. And, what I mean by "graffiti" is street art and writing that hasn't been legally commissioned (unlike the majority of what appears in the lead photo). Although it may seem counter-intuitive, as Suzi Gablik contends, graffiti "needs criminality to maintain its ethical quality, it's a note of authenticity."

A city without graffiti is surely a stolid place.

On the other hand, it's important to note that the wide-scale proliferation of graffiti has, historically speaking, been a sign of a city's lack of health -- of higher crime rates, a larger drug trade and/or general citizen apathy. New York City of the 1980s is a classic example of this tendency: as the amount of graffiti diminished in the late 80s, the crime rate soon followed.

One must, however, resist making direct and uncomplicated connections between these two trends. The sheer number of variables that play a role in the overall reduction of crime in a city make it virtually impossible to establish surefire links between discrete elements and the greater whole.

Nevertheless, I don't think it ridiculous that a mayoral candidate so vocal about cracking down on crime would target the elimination of graffiti as part of his platform. (What is ridiculous, however, is Mammoliti's suggestion that by-law officers carry guns to enforce petty crime). Graffiti, by its very nature, poses a threat to the institutional and disciplinary practices with which politicians are tasked.

Perhaps a useful analogy in this regard comes from the work of the French theorist Michel de Certeau. In the chapter "Walking in the City" from the The Practice of Everday Life de Certeau draws a distinction between two experiences of the city. When viewed from above (he uses the example of gazing upon New York from atop the former World Trade Center), one's perspective of the city is voyeuristic, totalizing and panoptic, much like vantage point a politician or any authoritarian must adopt in the process of governance.

The elected official -- here I refer to a mayor, but it would be true of a leader of a ward, province, state or country -- must have a rational, predictable and all-encompassing plan to ensure the socioeconomic success of his or her polity. Far from something sinister, this is the very nature of his or her occupation. And so, metaphorically speaking, he or she must view the city as if on high -- surveying its entirety from a distance that separates the viewer from what happens below.

Contrary to this, as de Certeau argues, "The ordinary practitioners of the city live 'down below,' below the thresholds at which visibility begins. They walk--an elementary form of this experience of the city; they are walkers, Wandersm채nner, whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban 'text' they write without being able to read it.... The networks of these moving, intersecting writings compose a manifold story that has neither author nor spectator, shaped out of fragments of trajectories and alterations of spaces..."

I view graffiti in a similar capacity. Just as the pedestrian, the so-called "man on the street," demonstrates an almost natural resistance to the regulatory strategies of urban planning -- think of grid-like streets, traffic lights, speed limits, "keep off the grass" signs, etc. -- the graffiti artist writes an alternate text of the city, one that counters the institutionally prescribed experience of urban life. Jaywalking, short-cutting, loitering and meandering, are all tactics we use -- knowingly or not -- to refuse being fixed or funneled into predictable, repeatable behavioural patterns. Similarly, the act of taking a can of spray paint to an alley wall reveals an inherent dissatisfaction with the city as planned by its official builders, be these politicians or developers.

Not merely the act of disenfranchised and alienated youth, graffiti is representative of the collective desire to cultivate autonomy within a system that so often structures choice along consumeristic lines. The tag, the stencil, the writing of graff -- these are little eruptions of dissent, usually harmless, but always a reminder that it's possible to "be otherwise," that other versions of the city exist.

For de Certeau, the spontaneity and resourcefulness of the urban walker is demonstrative of the degree to which individual citizens animate cities. Defined by flux, the urban environment is continually written and re-written by the everyday practices of its residents, many of which rub up against official policy. Doesn't graffiti fit into this mix? Cities are continually contested spaces, and writing on a wall is one of the many ways that citizens lay claim to their environment.

Is this conception of graffiti idealistic? Yes, without doubt. So many tags are uncreative, ugly and a nuisance to property owners. But even a brief perusal of a column like Torontoist's "Vandalist" reveals the potential of graffiti to enrich a city with impromptu art.

So forgetting the pragmatic oversights of Mammoliti and Bussin's proposals -- there are plenty of people over 18 who produce graffiti, parents shouldn't be held accountable for every law that their teenager breaks -- the question becomes, do we really want to live in a city that bans minors from buying spray paint, that takes a hard stance on graffiti and that overreacts to the quiet rebellion represented by wall art?

Councillor Bussin's proposal is based on a similar -- and putatively successful -- bylaw in London, Ontario. Still, I can't remember the last time I thought that Toronto should be more like London. Even anecdotes about the days of "Toronto the Good" or "New York run by the Swedes" conjure up images a hyper-clean but ultimately characterless city.

But, alas, being an advocate for graffiti is a little like walking a tight rope: every step of your argument may be the last before you say something stupid that reveals your hopeless naivety. As such, I don't claim to have a plan that could somehow eliminate the bad graffiti and keep only the good stuff (and, besides, do people even agree on what's good and bad graffiti anyways?). With graffiti, the delightful comes hand in hand with the dirty and distasteful.

And yet, it's undeniable that the attempt to eradicate unsolicited street art reveals a political ideology that seeks to compartmentalize, fix and regulate citizen behaviour in a manner that would make the average Torontonian -- graffiti supporter or not -- most uncomfortable.

Photos by marty pinker, sniderscion, spotmaticfanatic, ibid, andyscamera and Maryam S., members of the blogTO Flickr pool.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments