Downtown Heritage Battle Begets Hope and Despair

The fight to save Toronto's architectural heritage is a bitter one; passion is often the sole remaining motivation for so many fighters on the front line of this endless battle. This is a good thing, because it quickly becomes plain that reason and common sense don't stand a chance, especially in a system that's become increasingly stacked against them.

Over two years ago, a notice was put up in the window of a building on King Street East in Toronto's old downtown that a developer was seeking city permission to erect a condo on the site. This was the beginning of a battle for Robert Cishecki that continues to this day. A real estate broker and local resident, he's collected signatures and started a website to publicize the cause of forcing the city to enforce its own bylaws.

"Why are the citizens, the stakeholders, having to flip either for legal bills or hiring some kind of representation to defend the very laws that the city should be defending to begin with?" Cishecki asks me. "Why should we be defending the laws when we have politicians and bureaucrats and administrators to do that?"

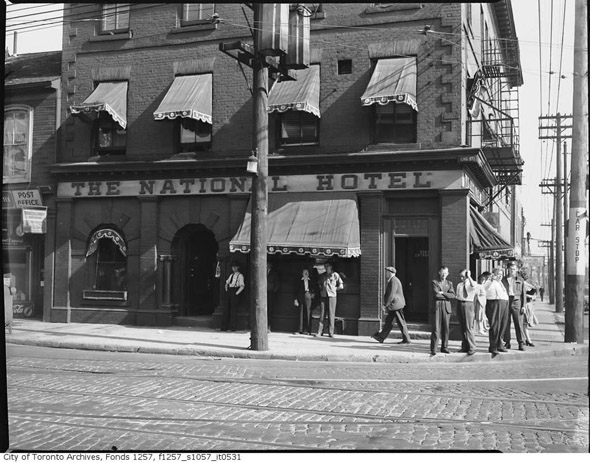

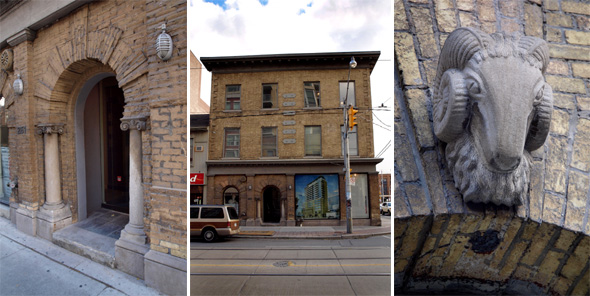

The building in question is solid but unspectacular, except for the massive arched doorways that give it an indelible street presence. Built around 1861, the buff brick three-story structure at the southeast corner of King and Sherbourne began life as an inn, and was photographed by the city between the two world wars doing business as the National Hotel. Today it's the home of a law firm, though the street level windows are covered with architectural renderings of the Bauhaus Condos that Rams Head Development plans to erect on the site, with the yellow brick skin of the original building wrapping two of its corners.

Rams Head is virtually invisible online, and the phone number on the business card I was given by the law firm's receptionist is no longer in service, but their bid to develop the site is forging ahead, in spite of Cishecki's best efforts to stop it. An application for rezoning conspicuously languished in council for 120 days, after which the developers were entitled to push it forward to the Ontario Municipal Board, who will begin pre-hearings on the project on the 17th of this month.

It should be noted that Rams Head is being represented by Aird & Berlis, the law firm that Cishecki calls "pitbulls of municipal planning," where David Miller was a senior partner previous to becoming mayor. It's the sort of detail that makes paranoia and despair a constant companion for heritage groups fighting to preserve buildings.

"You should go to the mat for that building," agrees Alec Keefer, acting president of the Ontario Architectural Conservancy and a longtime player in the city's heritage battles. He's not hopeful though, as he's seen the city ignore heritage designation time and time again, in favour of woeful compromises like ruefully-named "facadomies" where nothing remains but a few external walls.

"Toronto is still tearing down what other cities would enhance," says Michael Comstock, president of the Old Town Toronto alliance - the BIA/community group that oversees the city's historic downtown area. It was Howard Levine, the executive director of Citizens of Old Town Toronto, who coined the term "facadification" 12 years ago, Comstock recalls. "This is what will probably happen to the National Hotel. Toronto is still tearing down what other cities would enhance. Toronto only saves buildings here and there, like the Flatiron set against the modern bank towers. Hell, they stole Campbell House from Old Town to put it on display on University!"

"What I've found the Heritage Preservation Board to be is a buffer," Cishecki says, "to allow developers to get greater density and height under the auspices of keeping a facade." Originally, the board supported the complete demolition of the building, claiming that the brickwork was spalling. Cishecki happened to attend a public hearing, and drew on his years of experience renovating and restoring buildings to point out that it wasn't unsalvageable, and that he knew of a company in the U.S. that could help. This led to an about face and the faรงade-preserving redesign, but Cishecki argues that the city has to force developers to preserve historical buildings like 251 King, especially when they're protected by heritage bylaws that they've written.

"Respect the law, respect the laws that are there for all of us, and force the developers to respect the law."

Archival image of National Hotel courtesy of City of Toronto Archives.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments