A history of the Toronto Maple Leafs' first televised goal

It was 9:30 p.m. on Saturday Nov. 1, 1952 when the first scratchy monochrome pictures of the Toronto Maple Leafs flashed on to Canadian television screens. The evening broadcast had so far consisted of Tales of Adventure, Sporting Pastimes, and a movie, but the big moment had finally arrived - NHL hockey was on TV for the first time in English.

The newly formed CBC had been experimenting with camera angles and locations high in the rafters of Maple Leaf Gardens and the Montreal Forum for months. Unfortunately, when the broadcast finally live, the timing was awful.

It was 6:22 in the second period and Leafs' centreman Bob Hassard had just scored. The first shots showed the team embracing, leaving the viewers to rue what they had missed by a matter of seconds.

Broadcast hockey has its roots in the early 1920s and legendary announcer Foster Hewitt. The son of a Toronto Star reporter, Hewitt, a wireless fanatic, had taken a job with the newspaper in the hopes of scooping a position at CFCA, the paper's AM station.

It wasn't unusual for a newspaper to have an in-house broadcast division in 1922. The Toronto Evening Star and Globe and Mail both has radio vans to promote special events and their print editions. The broadcasts often lacked advertising because, according to Michael McKinley's history of Hockey Night in Canada, it was seen as intrusive.

The patient Foster Hewitt got his wish when his boss surprised him one evening with a special assignment. "I happened to be coming into the Star office around six o'clock at night and I had finished what I thought my work for the day," he recalled. "Bruce Lake, the radio editor of the Star, came up to me and said 'you have another job tonight: you're going to broadcast the hockey game.'"

"I didn't know enough to turn it down at the time, which I was rather fortunate I didn't, so I went over there and did the game. Unfortunately for me it went 30 minutes overtime."

As was customary at the time, Hewitt recapped the first two periods and called the third frame live from a tiny rink-side booth. The box was about three-feet square and was slightly raised to give a good view. Instead of a microphone, Hewitt delivered his commentary into a telephone with an open line to the radio desk.

The little glass booth was so cramped Hewitt spent much of his free moments wiping a letterbox-shaped window in the persistent condensation.

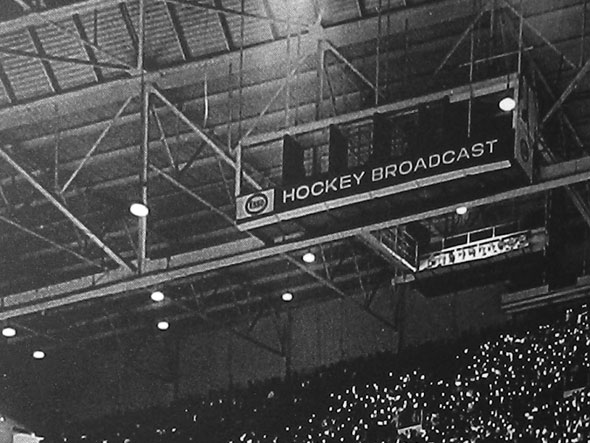

From his first foray into the Mutual Street Arena, Foster Hewitt eventually became the voice of Maple Leafs hockey and the official team's official announcer when they moved to Maple Leaf Gardens in 1931. His new perch was a purpose-built broadcast booth high in the metal rafters of the new stadium.

"The Gondola," named for its resemblance to the passenger cabin of an airship, was suspended 18 metres above the ice. To get in, Hewitt and his technicians had to make a terrifying ascent through the building's fan room, along a metal catwalk, and over and down a series of ladders high above the heads of the fans below. Though the gondola provided an excellent vantage point for live commentary, TV would reject it.

The visual possibilities weren't welcomed with a loving embrace by hockey brass. NHL president Clarence Campbell was worried televising live games would kill ticket sales. "The fast end-to-end rushes, the skillful, attractive features of the game are most difficult to portray because of TV's limited field of view. This is not a proper representation of the overall action, and certainly can't be doing the game any good," he told Hockey News in 1949.

Conn Smythe, then owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs, wasn't exactly blown away by TV's possibilities either. "If that's what hockey looks like on television, then the people of Toronto won't be seeing it," he said following a test filming in 1952.

Gerald Renaud, a CBC sports producer in Montreal, organized the first ever television broadcast of an NHL game that same year between the Canadiens and Red Wings with commentary in French. The grainy black and white video featured the Habs' legendary "Punch Line" - Maurice "Rocket" Richard, Elmer Lach, and Toe Blake - and the Detroit's Gordie Howe.

Renaud had tested his three-camera configuration filming ping-pong games for the fast back-and-forth action. In the end he settled on one camera with a wide angle lens to capture the entire ice surface, another for medium shots, and a close-up camera for action in the centre ice face-off circle and around the nets, a system still in use today.

George Retzlaff, a fellow CBC producer, followed Renaud's set-up when he was charged with televising the first English language hockey match from Maple Leaf Gardens a few weeks later. Instead of perching the unwieldy cameras in Foster Hewitt's gondola, which Retzlaff believed would make game look like it was being played on an slope, the Marconi machines were placed lower, roughly level with the centre line.

The picture wasn't always clear enough to pick out the tiny vulcanized rubber puck among the melee of sticks and skates - it was even harder to follow the speeding disc as it zipped around the ice - but the early broadcasts were certainly watchable, especially with Hewitt's radio play dubbed over the top.

Hewitt's vocal trademarks are still recognizable to modern hockey viewers. His signature welcome, "hello hockey fans in the United States and Newfoundland," still graces the start of Hockey Night in Canada. "He shoots, he scores" has been copied by countless broadcasters.

As would be the custom until 1968, the fledgling CBC joined the Leafs action in the second period moments after Bob Hassard had scored the first goal of the game against the Boston Bruins' Jim Henry. The players were congratulating each other, the crowd was screaming, but the TV audience was confused.

It would take eight more minutes for Max Bentley to score the first ever televised Maple Leafs goal, giving the home team a 2-0 lead they would eventually parlay into a 3-2 win. Despite the victory, the team would go on to finish 5th in the NHL that year, in front of only the dismal New York Rangers.

Hockey Night in Canada became a nationwide phenomenon. Player interviews, quizzes, highlight tapes, and even orchestral music filled time between periods and sponsorship made the enterprise financially viable.

In 1955, a new process for rapidly developing 16mm kinetoscope film would deliver another landmark moment in televised sports: the first ever instant reply. Ever the pioneer, George Retzlaff employed a new "hot processor" capable of rapidly developing film during Hockey Night broadcasts

A member of the production team would record the match, cut the tape after a goal, and quickly load it for playback, often within 30 seconds.

Before the processor, it could take hours or even days for games to be shown on repeat. Now all Foster Hewitt had to do was wait for the cue and link to a quick repeat of a Ted Kennedy slapshot or a Tim Horton hip check.

Finally, Toronto could watch the Maple Leafs score over and over again.

Chris Bateman is a staff writer at blogTO. Follow him on Twitter at @chrisbateman.

Images: City of Toronto Archives

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments