Toronto through the lens of Patrick Cummins

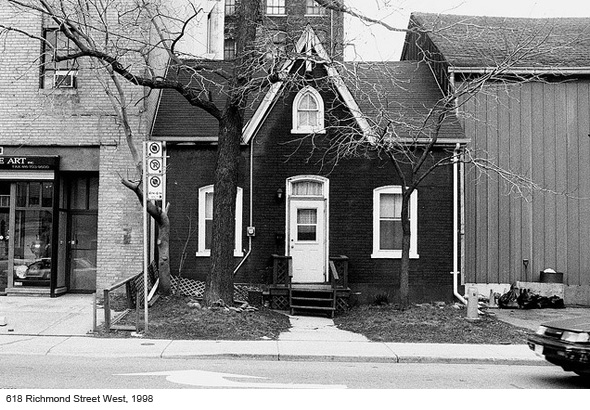

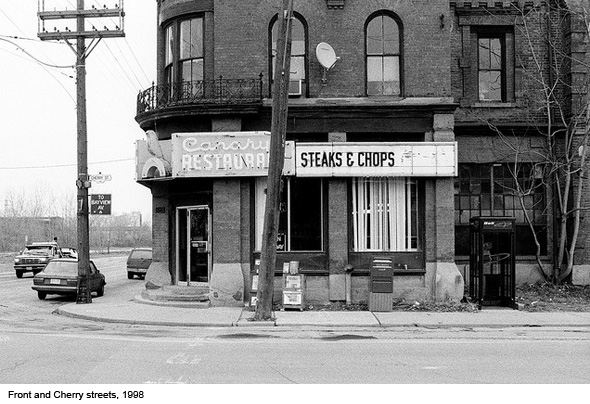

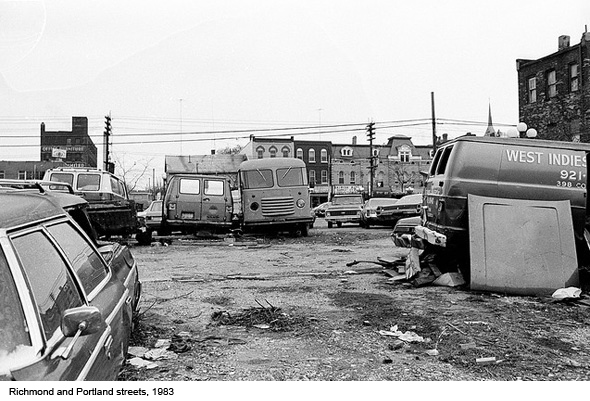

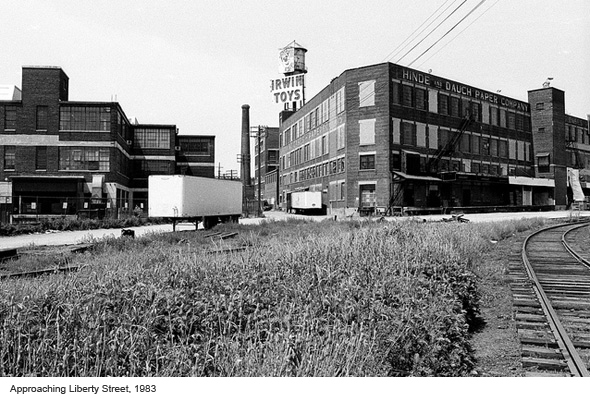

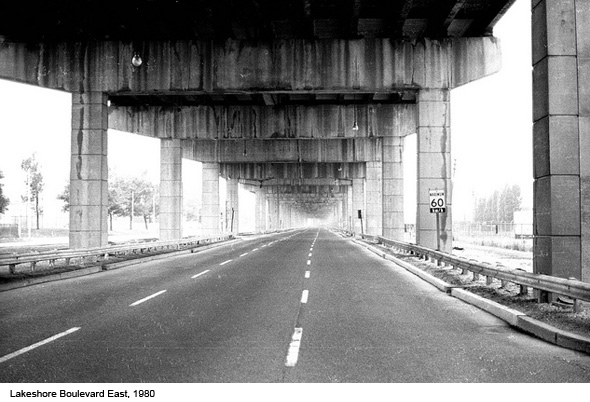

For the last 30 years or so, Patrick Cummins has documented Toronto's changing streetscape. A thoroughgoing exercise if there ever was one, few collections rival the breadth of his ongoing project, which takes the city's vernacular architecture as its main subject. Not one for shooting monumental structures, Cummins' work offers a window into a side of Toronto that's easily lost to the grand narratives that tend to underwrite our understanding of urban evolution.

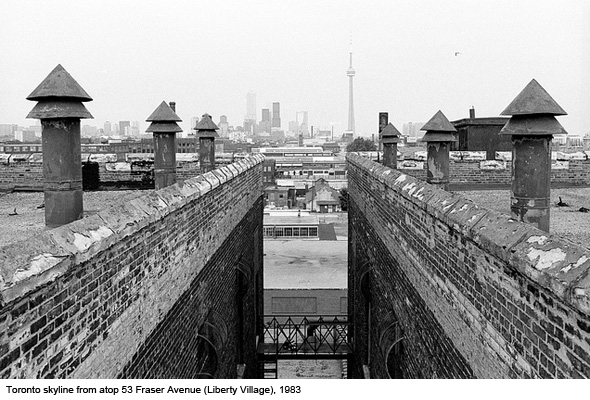

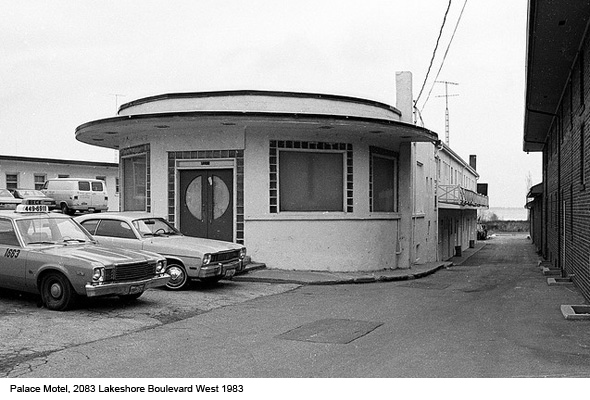

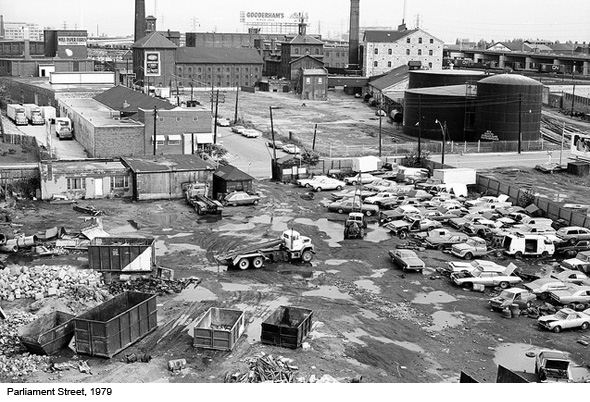

It's also easy to lose whole afternoons searching through page after page of his photos on Flickr. Immaculately organized and labeled, his images capture both the gradual shifts the streetscape constantly undergoes â the faded signs, the fresh coats of paint â and the more profound changes that happen over decades. If you've ever been curious about what Liberty Village looked like before the condos or what the Distillery District looked like before its rebirth as a tourist site, satisfaction awaits in the perusal of Cummins' work.

Earlier this week I spoke with the photographer about his project, his upcoming book, and the crucial role that Toronto plays in his artistic practice.

At last check, your Flickr photostream has over 23,000 images. When did you start taking photographs and why?

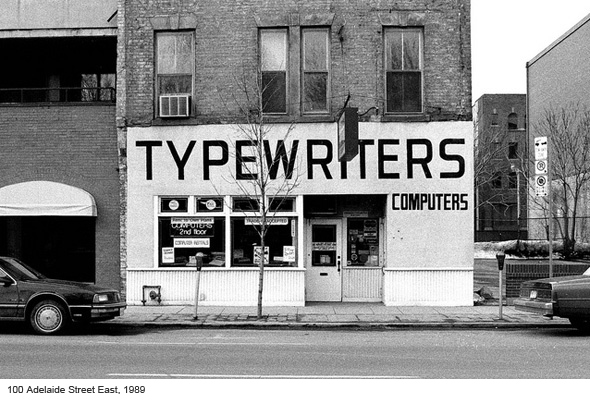

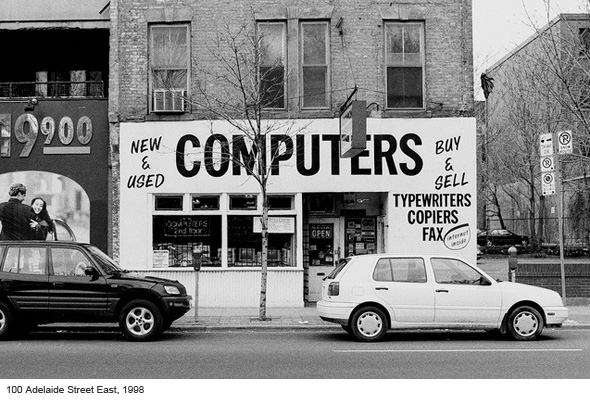

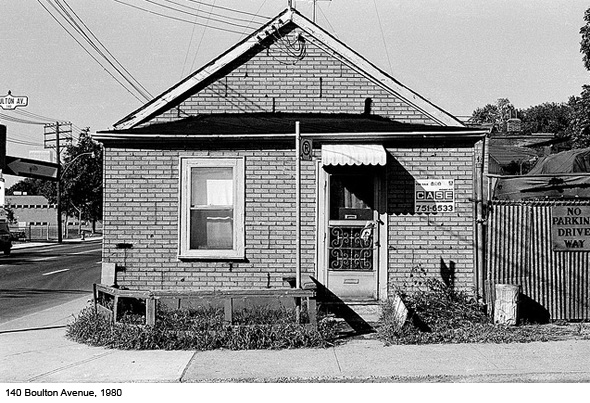

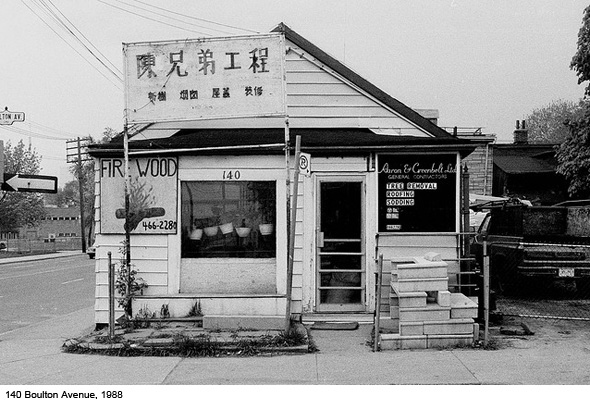

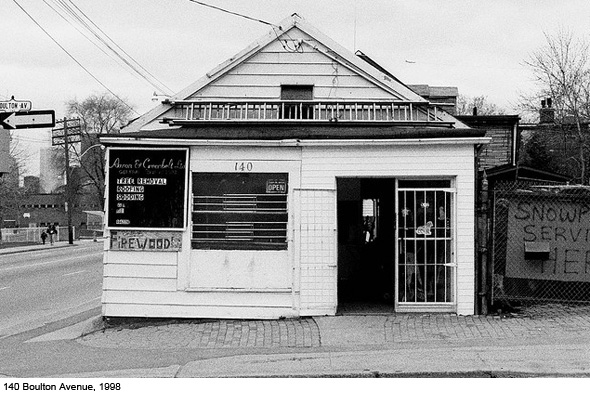

I bought my film camera, a Nikon F2, in 1977. I began to photograph aspects of Toronto's streetscapes when I moved here in the summer of that year to attend the Ontario College of Art. I had discovered the work of Walker Evans and Eugene Atget and I was interested in documenting signage and various building types that I was seeing on the streets of Toronto. It wasn't until 1988, however, that I had my epiphany and my comparative studies project got underway in earnest. I realized at that time that I had reshot some structures at different points documenting very drastic changes in some and rather subtle changes in others and I decided to look at ways in which I could expand upon that documentation in the form of a full-fledged project which I call "Collations."

As for my Flickr photostream, it is just that, a stream, a stream-of-consciousness record of what I've been scanning of my older work mixed up with what I'm currently shooting. It's a grab bag of this is what I've done and this is what I'm doing, what I'm thinking, and what I'm noticing, but the Collections and Sets do break the stream up so that it's a little more understandable as to what I've been doing over the decades even if the Flickr interface itself isn't always the best format for presenting the work.

You're an archivist by trade. Can you tell me how this has informed your photographic practice?

Not to say that there won't always be those interested in studying Toronto's history on a grander scale, but working in archives I find that overall, more often than not, researchers are more interested in the street-level aspects of the city...their house, their street, their neighbourhood...than they are in the grand and/or monumental. I guess working in an archival setting has impressed upon me the ephemeral nature of our built environment, how it is constantly changing, in ways both subtle and drastic at every level, not just on a grand scale. Working in archives caused me to think about photographic documentation in an urban setting in ways beyond a simple documentation of what's there now to a documentation of what's there over time, and to look more at the peripheral and the interstitial when it comes to our built environment.

Do you see your work exclusively in an archival capacity? Or would you say there's a fine art element to what you do as well? Perhaps this is a false dichotomy since the rise of Bernd and Hilla Becher, of whose work I'm reminded when I see your images presented in grid format.

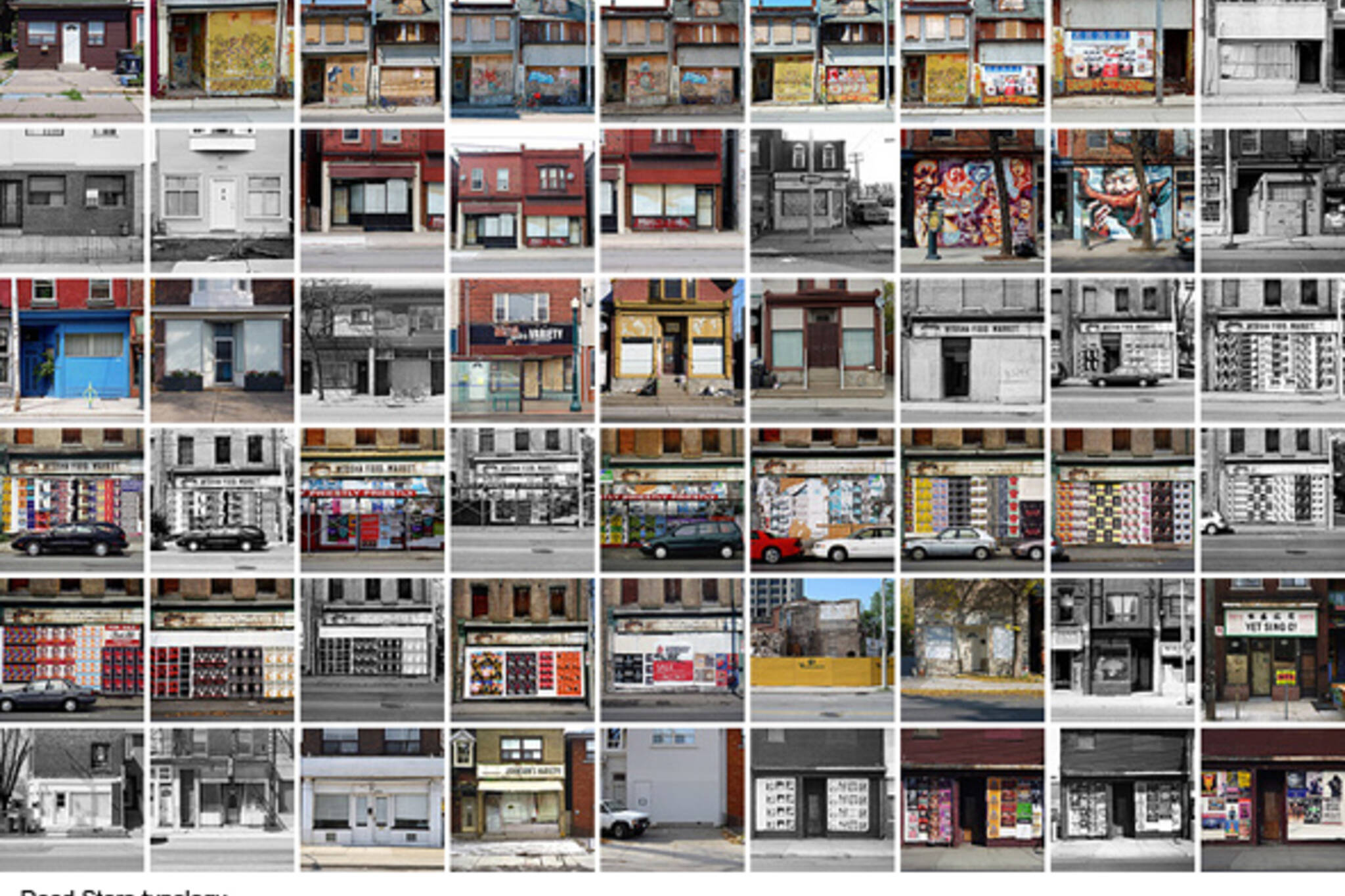

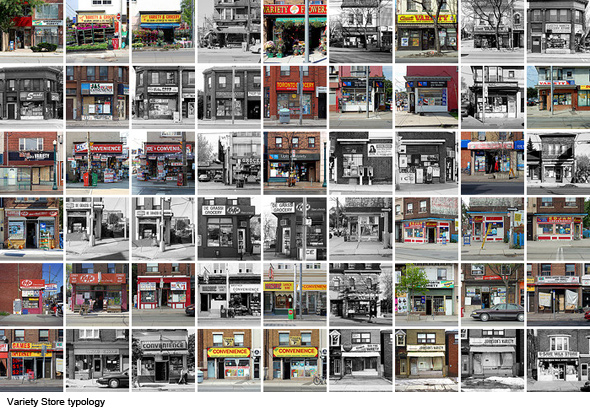

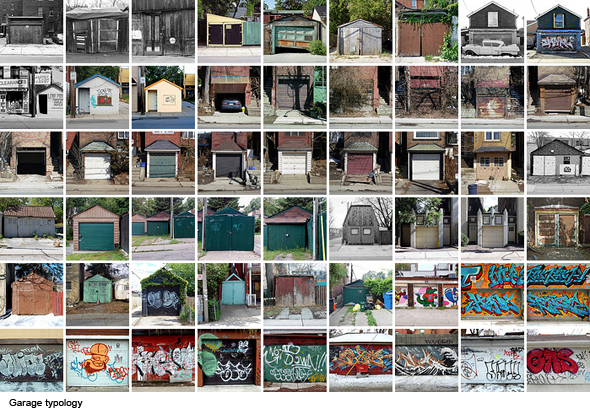

I think the work has always involved elements of documentation filtered through ideas about how photographs can be viewed or read in gallery or published formats. Early on I struggled to situate myself within the context of cultural theories regarding photographic practice. This did lead me to pursue a photographic practice in multiple images, in grids, which is still my preferred method for presenting my work, and the Bechers are a touchstone in that regard, but ultimately I was never able to establish myself in any way where the work would support me, so I pursued other options, obtaining work in the archives field.

Working in archives provided me with a reliable income to pursue my work and another framework within which to think about photography. I made a decision at an early point to just work at creating a body of work and not worry about showing it or trying to fit into any contemporary scene, and I only began to show my work again more recently, with the arrival of CONTACT and Flickr opening up options for sharing one's work outside of the gallery context. That being said, my work has from time to time found itself comfortably ensconced in exhibitions coming from of both art and documentary perspectives, and I do have work in the holdings of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in Ottawa, a program of the National Gallery of Canada.

In Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York, authors James and Karla Murray argue that the mom and pop type shops they document "have the city's history etched into their facades." As you said, you tend to shy away from the documentation of Toronto's monumental structures in favour of what might be called the commonplace. Can you tell me about this decision/strategy?

I'm a big fan of their work, with this book and their others. I consider them kindred spirits of a sort. I too am impressed with the layering of histories on the patina-enriched surfaces of Toronto's commonplace streetscapes. In my work I have extended my documentation of these streetscapes beyond the commercial stretches into the residential streets of the downtown core, and I've taken it to a level beyond the here-and-now by doing comparative studies of structures over time, in some ways not unlike the work of Camilo Jose Vergara. As to why I focus on the commonplace vs the monumental, it was a decision made early on based on my affinity for the commonplace and my love of the work of Evans and Atget and others who have followed in their footsteps in celebrating the everyday urban vernacular.

You're at work on a book. Can you tell me a little bit about it?

It's being published by Coach House Books and it'll be launched in May as part of the 2012 Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, with an exhibition at the Urbanspace Gallery at 401 Richmond Street West. It's called Full Frontal T.O.: Exploring Toronto's Architectural Vernacular, and it contains photographs by myself and words by Shawn Micallef, author of Stroll: Psychogeographic Walking Tours of Toronto. The book is a celebration of that messy urbanism that makes up a city like Toronto, and how it shifts and changes with the passage of time. It'll contain a series of comparative studies of structures over time in black and white interspersed with full colour sections containing typologies of various elements of the built environment such as variety stores and laneway garages.

Your photos have captured many areas of the city that have undergone profound change over the last 15-20 years. Can you highlight a particular neighbourhood in which this is apparent from your photographs?

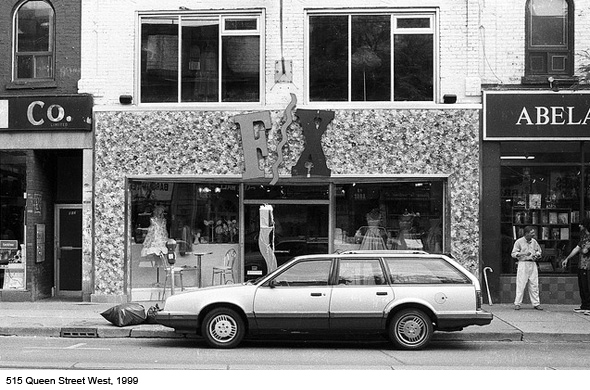

The obvious choice here is Queen Street West. It was the central focus of my photographic activities when I started in the late seventies and it continues to play an important role in what I do today. When I started, the street was just beginning to be gentrified in the stretch between University and Spadina. It continued westward to Bathurst in the 1980s and then things quietened down.

More recently, however, there has been a boom in activity west of Trinity Bellwoods, as the gentrification process continues its relentless march ever further westward, causing the streetscape to undergo big changes. The other big change that's occurred has been the complete erasure and/or re-writing of the city's 19th century industrial landscape, with the shift from loft living as we knew it in the 1980s to the condominium explosion of today. Liberty Village in the west and the Distillery District and the West Don Lands in the east are two areas that I documented in the 1980s that have undergone vast transformations.

Film or digital? Or, if formerly film, when did you make the switch to digital and why?

I'm shooting less and less film and more and more digital. Although I continue to shoot most of my re-shoots of structures for my Collations project on film, and I will continue to do so for as long as I can, I have a lot of other, colour projects on the go, and for these, I shoot digital. For more than a year, I was without my film camera as it was in the shop being repaired and re-calibrated. The point-and-shoot film camera with which I had begun my colour side projects had died. So I bought a point-and-shoot digital, and followed that up rather quickly with a Nikon D40 SLR, and I've continued on from there.

Shooting digital is, of course, very different than shooting film. Not so much because you can see what you did or didn't get right away, but more because it's so inexpensive and you can shoot so many more images at a time than you could with film. Much of the pre- and during-shooting editing involved with shooting film is gone, replaced with huge editing efforts coming after the fact. And by editing, I'm not talking so much about editing the individual images as I am about editing images into meaningful groupings or contexts.

In the end, I'd say I'm a firm believer that interesting work can be produced using pretty much any combination of equipment and techniques, with the content of photographs and how they are contextualized also being of utmost importance.

Do you think you'd be as motivated to continue your photographic work if you were forced to change cities for some reason? In other words, is there something about Toronto or your relationship with the city that sustains your desire to keep shooting?

Toronto is definitely my subject matter and will remain so as long as I can document it. The city and my documentation of it are inextricably intertwined at this point. However, I think if I was forced to move to another city, the drive to document would prevail in that new setting. I would pretty much photograph the same subject matter. I would immediately try to capitalize on that stranger in a strange land advantage one has to seeing another city for the first time by identifying elements that stood out to me, and then begin to pursue a documentation of them in such a way that I could build up a body of comparative studies over time like I have with Toronto.

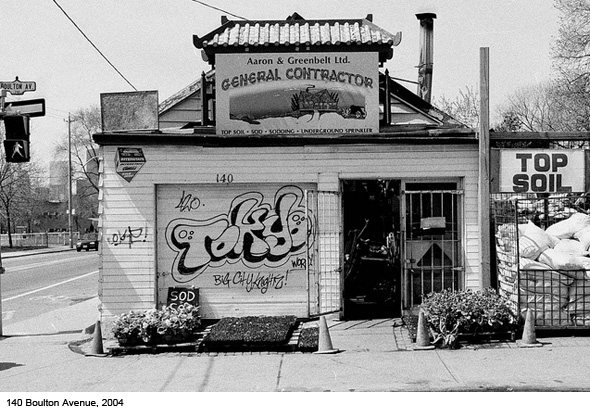

140 Boulton Avenue

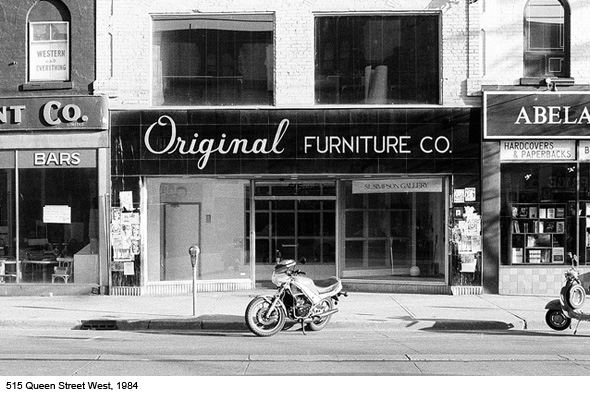

515 Queen Street West

The photographer at work

All photos by Patrick Cummins, more of whose work can be seen here.

Latest Videos

Latest Videos

Join the conversation Load comments